This is an automatically translated article.

The article is written by Dr Department of Medical Examination & Internal Medicine, Vinmec Central Park International General Hospital

Intestinal metaplasia of the stomach is a precancerous lesion in the course of chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma. This is the most important precancerous stage of stomach cancer, so a stomach biopsy will help diagnose stomach cancer early, bring positive effects in the treatment of the disease later.

1. Outline

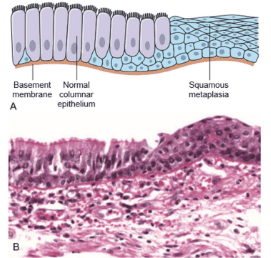

Metaplasia (metaplasia) is the regenerative change of one type of mature cell (epithelial- or host-mesenchymal) to be replaced by another cell type. It is the adaptation of the cell to stress by a different type of cell that is able to withstand the change of the new environment.

Genetically, metaplasia is the reprogramming of epithelial stem cells or of undifferentiated tissue host cells in the connective tissue.

An example of epithelial metaplasia is the laminar transition of the respiratory system in smokers. The hairy columnar cells in the trachea are partially or extensively replaced by stratified squamous epithelial cells. Vitamin A deficiency causes similar changes in the respiratory system.

Despite the adaptive function, the normal vital protective functions are lost such as mucus secretion and the barrier of micro-substances from entering the respiratory system. Thus epithelial metaplasia is a double-edged sword. Prolonged metaplasia leads to carcinogenesis.

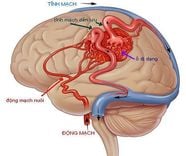

Metaplasia does not necessarily translate from columnar epithelium to squamous epithelium. As in chronic acid reflux, the squamous epithelial cells in the lower third of the esophagus will metaplasia into intestinal epithelial cells (Figure 1).

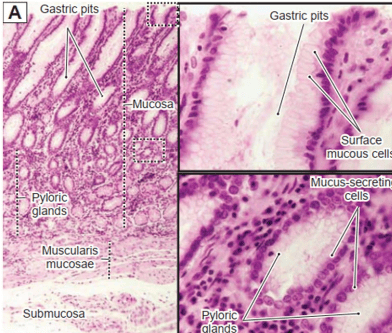

1.1 Histological structure of the stomach

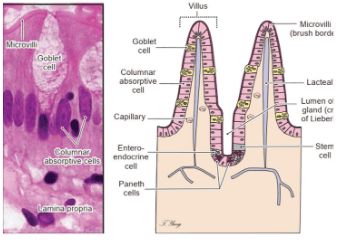

1.2 Histological structure of the small intestine

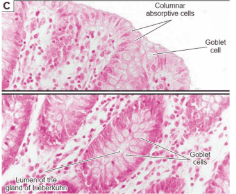

The top of the cell is covered by Microvilli (brush border) Goblet cells: mucus-secreting cells Columnar absorptive cells: enterocytes

The top of the cell is covered by Microvilli (brush border) Goblet cells: mucus-secreting cells Columnar absorptive cells: enterocytes

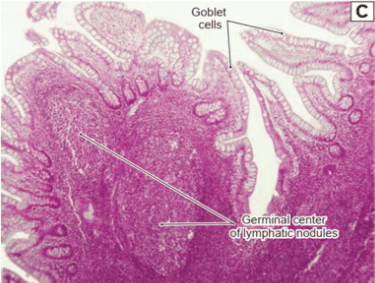

1.3 Histological structure of the colon

Columnar absorptive cells: enterocytes Goblet cells: mucus-secreting cells. The top of the cell is not covered by Microvilli (brush border)

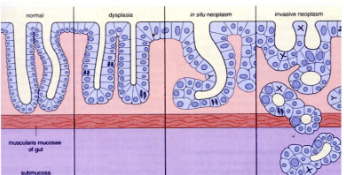

1.4 Dysplasia

Dysplasia: This term is used to describe histologically showing structural changes, increased cell division with incomplete maturation. Metaplasia can progress to cancer (neoplasia) (Figure 8).

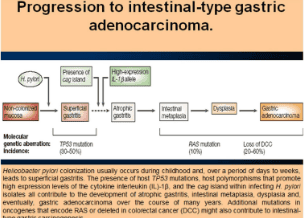

2. Gastric intestinal metaplasia

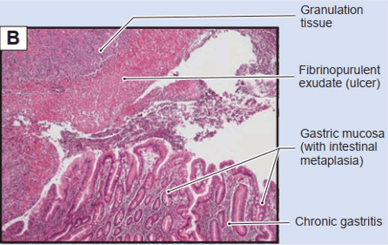

Intestinal metaplasia of the stomach is a precancerous lesion in the progression of chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma (Figure 9).

The risk of cancer is there but not high. There is a need for new markers and advances in endoscopy to help detect and understand the time to follow the progression of intestinal metaplasia.

2.1 Definitions

Intestinal metaplasia is the replacement of gastric glandular epithelium by intestinal epithelium.

2.2 Subtypes

Because intestinal metaplasia is diverse, there are many ways to classify it:

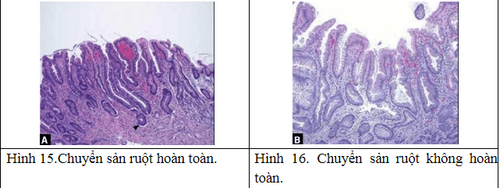

Based on the extent of spread over the stomach, metaplasia is divided into: Localized metaplasia: limited to one region of the stomach, Extensive metaplasia: in at least 2 regions, the body and at least the antrum or small curvature (the boundary between the vertical and the transverse small curvature). A clinical classification based on hematoxylin eosin staining is divided into: Complete metaplasia: with small intestinal mucosa with goblet cells, brush borders and eosinophilic enterocytes. Incomplete metaplasia consists of the colonic mucosa with numerous mucin droplets of irregular size and without a microvillous (brush border). There is another classification based on Alcian blue and high-iron diamine staining to distinguish mucin and metaplasia: Type I (complete): sialomucin-only metaplasia; Type II (incomplete): mucin is a mixture of gastric mucin (neutral) and sialomucin; Type III (complete): with sulfomucin.

2.3 Epidemiology and risk factors

Correa's Cascade shows coordination between host genetics and responses. While metaplasia can be a reversible change, it is usually a cancerous change. In general, the risk factors for gastric metaplasia are similar to those of gastric cancer such as chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori, host and response genotypes, high-salt diet, smoking, alcohol consumption and Chronic bile reflux.

Worldwide we do not have the frequency of intestinal metaplasia but can take the frequency of gastric cancer. A large US census of more than 895,323 upper gastrointestinal endoscopy samples showed a frequency of intestinal metaplasia of 4.9%. In Sweden with 300,000 cases is 4%. In the Netherlands it is 7%.

2.4 Clinical symptoms

In general, intestinal metaplasia causes no symptoms and is usually caused by patients undergoing colonoscopy and biopsies because of dyspepsia. Metaplasia followed by oligospermia leads to SIBO (Small Bowel Bacterial Overgrowth) causing abdominal distention, discomfort and diarrhea.

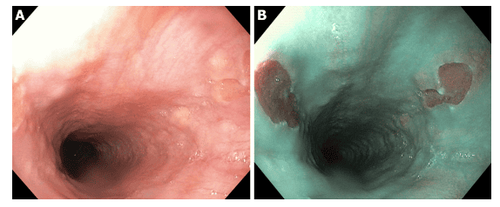

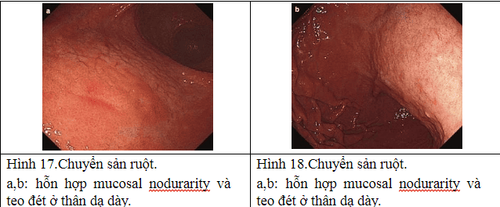

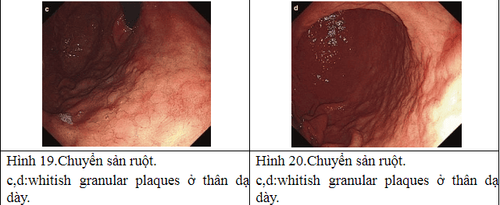

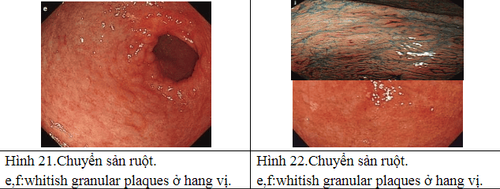

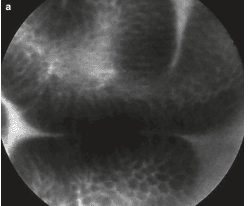

Under endoscopic white light intestinal metaplasia without specific symptoms. The area of metaplasia appears as a pale or rough area.

2.5 Diagnosis

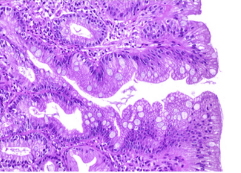

Diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia is based on histology of the biopsy specimen showing that the glandular mucosa is replaced by the mucosa of the small intestine or large intestine.

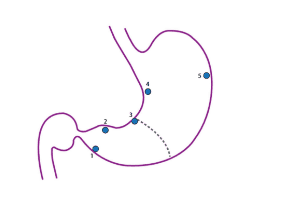

Evaluation and classification of intestinal metaplasia: when reading the specimen, it is necessary to determine the severity and type of intestinal metaplasia (complete or incomplete) to see the risk of gastric cancer and have a follow-up direction. Evaluation requires biopsies of at least 5 areas (gastric mapping) (Figure 12).

Usually, 3 years later, do the mapping again.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy mapping: biopsy mapping is beneficial in monitoring and should be performed in 5 areas (Figure 12).

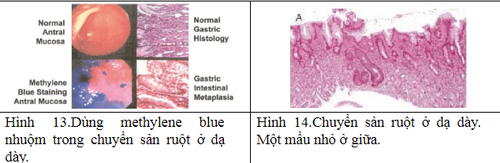

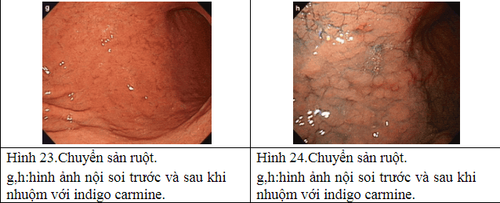

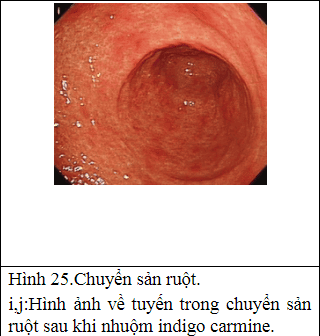

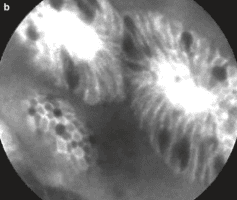

Other imaging facilities: + Magnification chromoendoscopy: only available in specialized centers, especially in Asia. The principle is to use dyes to define histological features. There are many dyes such as methylene blue, acetic acid but the most popular is indigo carmine. Needs good training and a long execution time.

+ Narrow band imaging (NBI): is an endoscopic technique with high resolution to examine the structure of mucosal surfaces without the use of dyes. This technique can be combined with magnifying endoscopy to view the mucosal surface and vascular structure. A light blue crest pattern suggests intestinal metaplasia. The combination of these two techniques has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 93%.

+ Confocal endomicroscopy: helps detect early cancer but does not evaluate intestinal metaplasia. The principle of confocal microscopy is to emit a low-energy laser and measure the amount of reflected image from the tissue.

Intestinal metaplasia is a precancerous lesion similar to chronic atrophic gastritis.

2.6 Natural progression

Intestinal metaplasia is the most important precancerous stage of gastric cancer. The first point of metaplasia occurs between the gastric body and antrum, usually in the incisura angularis. As it progresses, the area of metaplasia enlarges and merges in the antrum and the stomach body.

When atrophy and metaplasia replace normal glands, decreased gastric secretion leads to hypoacidity and decrease in the amount of pepsinogen secreted by the main cells of the stomach body and increased gastrin by G cells. The first gastric mucosa resembles the cells of the small intestinal mucosa. In more advanced stages, the cells resemble colonic mucosa. Between areas of intestinal metaplasia there are regions of dysplasia.

Cancer risk: Patients with intestinal metaplasia have an increased risk of gastric cancer, but this risk is low in low-cancer areas such as North America and Eastern Europe. Cancer progression rates varied from 1.1. up to 2.0 for 1000 people/year and 3.0 for metaplasia.

The severity and rate of malignancy depend on the severity of Helicobacter pylori infection, environmental factors, genetic status, and type of intestinal metaplasia.

2.7 Treatment

The goal of treatment is to reduce the risk of stomach cancer by screening, eradicating

Helicobacter pylori and monitoring the cancer.

Elimination of Helicobacter pylori: eradication will result in histological changes in gastritis but not in intestinal metaplasia but may slow progression of gastric cancer. In patients with intestinal metaplasia treated endoscopically for early gastric cancer, eradication reduces the rate of cancer recurrence. Follow-up: In patients with extensive intestinal metaplasia (extensive) or incomplete metaplasia, endoscopic white light and biopsy mapping are required after 2 or 3 years. In other patients at high cancer risk, follow-up is individualized. Follow-up can reduce cancer and increase survival rates.

2.8 Chemical Prevention (Chemoprophylaxis)

There is no evidence of this in patients with intestinal metaplasia. Despite this, there is research showing that NSAIDs reduce cancer and slow the progression of intestinal metaplasia with celecoxib. There are no studies on antioxidants such as vitamin C or beta-carotene.

To detect the risk of stomach cancer early, you should have regular health checkups. Periodic health check-ups help detect diseases early, thereby planning treatment for optimal results. Currently, Vinmec International General Hospital has general health checkup packages suitable for each age, gender and individual needs of customers with a reasonable price policy, including:

Health checkup package general Vip Standard general health checkup package Patient's examination results will be returned to your home. After receiving the results of the general health examination, if you detect diseases that require intensive examination and treatment, you can use services from other specialties at the Hospital with quality treatment and services. outstanding customer service.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.

REFERENCES

Kumar V et al: Cell injury, cell death, and adaptations in Kumar, Abbas, Aster (eds): Robbins Basic pathology. 10th edition. Chapter 2. pp. 60 . Elserver. 2017. Stevens A – Lowe J: Neoplasia in Stevens A – Lowe J (eds): Pathology. 2 second edition. pp.89. Mosby. 2000. Morgan D: Gastric intestinal metaplasia in UpToDate 2019. Jencks DS et al: Overview of current Concepts in Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 14:92-101. 2018. Cui D et al: Atlas of Histology with functional & Clinical Correlations. Lippincott Williams & Wilkin. pp. 290-299. 2011. Brian Fennerty M: Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia on Routine Endoscopic Biopsy. Clinical Management. Gastroenterology. 125: 586-590. 2003. Capelle LG et al: Narrow Band Imaging for the Detection of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia and Dysplasia During Surveillance Endoscopy. Original Articles. Dig Dis Sci. 55: 3442-3448. 2010.