This is an automatically translated article.

The article was written by MSc Vu Duy Dung - Doctor of Neurology, Department of General Internal Medicine - Vinmec Times City International Hospital.Viruses are a common cause of encephalitis, with a variety of factors influencing the epidemiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of the disease. Host immune status is a core factor for herpesvirus infection of the CNS. This section focuses on CMV, EBV, and HHV6, viruses that can cause encephalitis in the setting of organ transplantation and immunosuppression.

1. Epstein-Barr Virus

EBV infection is common in children and generally resolves spontaneously with mild or no symptoms. The most common clinical presentation of the disease is infectious mononucleosis presenting with fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, and diarrhea.

Rarely, EBV can infect the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system, causing a heterogeneous group of clinical syndromes. Neurological infections are most often caused by latent viral reactivation in the setting of severe immunosuppression.

Neurological manifestations include encephalitis, meningitis, acute cerebellitis, cranial and peripheral neuritis, and transverse myelitis. Meningitis and EBV encephalitis are the most common neurological manifestations of EBV infection and have been reported mainly in children and adults following solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Most cases have a subacute progression of neurological impairment with heterogeneous symptoms, including headache, dizziness, ataxia, hemiplegia, brainstem syndromes, confusion, seizures, and changes in vision.

2. Diagnosis

The diagnosis of EBV encephalitis is confirmed by detection of EBV DNA in CSF and serum by PCR assay. The significance of EBV DNA in CSF is unclear, as EBV remains latent in nervous system lymphocytes and can be detected in healthy individuals.

However, the literature supports the diagnostic and prognostic usefulness of EBV load monitoring in CSF and peripheral blood following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. One study suggested that plasma present a better source for evaluating EBV disease or monitoring treatment response than peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Serological testing for EBV antibodies must be interpreted with caution. Serological tests include viral envelope protein IgM, viral envelope protein IgG, early antigen, and Epstein-Barr antigen. Positive viral envelope antigen IgM but absence of Epstein-Barr antigen indicates acute EBV infection.

Similarly, elevations in viral envelope antigen IgG levels tend to indicate an active EBV infection. Viral envelope antigen IgG and early antigen positivity may indicate that the patient has current or recent (within 2 months) EBV infection.

Finally, if viral envelope protein antigen IgM is negative but viral envelope protein IgG and Epstein-Barr antigen are positive, it is likely that the patient has had a previous EBV infection.

Brain MRI may be useful as an adjunct diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of EBV encephalitis. MRI very often shows symmetric T2 hyperintensity in the deep gray matter, brain stem, corpus callosum, and spinal cord. There are also reports of increased enhancement and localized edema in the brain which may, at times, have limited diffusion.

A 2017 case series also described patients with isolated, diffusely restricted and reversible clamshell lesions; These patients improve after 10-14 days of antiretroviral therapy.

It is not uncommon for patients to have a perfectly normal MRI. Longitudinal follow-up studies have generally demonstrated that MRI lesions eventually disappear.

3. Treatment

There are no guidelines and no licensed drugs for the treatment of EBV encephalitis. Expert practice and case reports suggest immediate use of antiviral therapy in combination with immunosuppression.

It is important to note that acyclovir has been tested for the treatment of infectious mononucleosis with no benefit. A 2017 randomized controlled trial showed promising results with valganciclovir in terms of inhibition of EBV replication and oral viral shedding.

There is no evidence to support the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of EBV encephalitis. The prognosis of CNS EBV infection is good, with 85% of patients returning to pre-infection baseline.

4. Cytomegalovirus

Humans are the sole reservoir of CMV, with nearly 60% of virus carriers in developed countries and 100% in developing countries. Transmission requires direct contact with saliva, blood, vaginal secretions, semen, or milk. Sexual contact, physician-induced exposure, and low socioeconomic status are risk factors for contracting the virus. Continuous viral replication in infected organs, including the brain, is one hypothesis for the severity of infection, especially in congenital CMV infection in neonates.

The histopathological criterion for CMV infection is a nuclear inclusion, although biopsy is not usually used because of the availability of advanced tests.

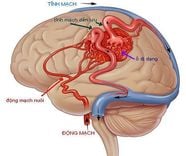

Viral DNA testing has identified the virus in monocytes, granulocytes and endothelial cells; Any of these reservoirs could be a reservoir for the virus to enter the central nervous system. CMV enters the CNS through viral spread in the blood into the base of astrocytes and near neurons or through infected endothelial cells on the surface of the meninges or central canals.

These main modes of viral entry explain why the histological manifestations of CMV are necrotizing encephalitis, nodular encephalitis, local parenchymal necrosis, and radiculitis.

5. Congenital and neonatal cytomegalovirus infection

Congenital CMV infection is usually asymptomatic at birth, but infected infants are still at risk for neurological impairment within the first 2 years of life.

Symptomatic infantile CMV disease is characterized by multiple organ involvement, including hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, retinitis, punctate and mottled haemorrhage, and hyperbilirubinemia.

Nervous system damage in congenital viral infections leads to microcephaly and intracranial calcifications. Infants who survive infancy experience hearing loss, motor delays, seizures, language delays, and chorioretinitis.

Progressive sensorineural hearing loss is the most common disability caused by congenital CMV infection and the second most common cause of neurosensory hearing loss in children. Diagnosis of CMV infection in neonates is by urine and saliva testing for CMV DNA.

Serological testing for the virus in the blood is also used to identify the disease and stratify the risk of later hearing loss. Antibody tests in the blood have no role in diagnosing CMV. Treatment of congenital CMV infection is 6 weeks of intravenous ganciclovir; however, foscarnet is being used more because of better central nervous system penetration.

6. Cytomegalovirus infection in adults

CMV infection in adults mainly in immunocompromised people; It is an important cause of infection in HIV-infected patients. Patients with AIDS are susceptible to the same lumbar polyneuropathy that causes pain from CMV infection.

Manifestations of polyneuropathy in AIDS patients include progressive subacute progressive paralysis of the legs that eventually leads to flaccid paralysis. Lumbar puncture showed granulocytosis and increased protein but low glucose. The definitive diagnostic test is PCR that detects CMV in CSF or damaged organs.

CMV encephalitis is rare and commonly seen in AIDS patients or stem cell transplant recipients and is caused by profound T-cell depletion. Patients will present with subacute cognitive impairment, cortical dysfunction brain, lethargy, and seizures. Brain MRI can be useful in diagnosing encephalitis and often reveals punctate, nodular, and diffusely restricted lesions.

The most common lesions are supratental and subependymal, but may be subcortical and subtentorial. Intriguingly, these lesions have limited diffusion for long periods, including lesions in periventricular sites where cytotoxicity persists. Mortality from CMV encephalitis is high, and treatment is usually limited to foscarnet because of ganciclovir resistance in transplant recipients.

7. Human Herpesvirus 6

HHV6 is ubiquitous in the human community, with close to 80% seroprevalence worldwide. Viral infections mainly occur during the neonatal period. HHV6 DNA was detected by PCR in saliva, suggesting it is a major mode of transmission.

HHV6 infects many cell types, including T cells, monocytes, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, oligodendrocytes, microglial cells, and astrocytes. Autopsy demonstrates the presence of HHV6 DNA throughout the brain in immunocompetent subjects.

Similarly, HHV6 DNA can be seen in CSF in up to 30% of children with a history of infection, raising questions about the usefulness of this test in diagnosing CNS infections.

HHV6 primary infection is an acute, self-limiting illness in infants and young children called roseola. High fever is the most common symptom, accompanied by lymphadenopathy and pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, and eardrum inflammation.

The clinical criterion for roseola is the appearance of a measles-like rash after the fever subsides. Neurological manifestations of the disease are rare in primary infection. Rarely, children may have febrile seizures; however, this is likely not a direct result of HHV6 infection, as similar rates of seizures occur in other childhood viral illnesses.

HHV6 reactivation in adults is seen in post-transplant patients with severe depletion of T-cell counts. The clinical presentation of the disease is paroxysmal limbic encephalitis, known as posterior acute limbic encephalitis. organ transplantation (PALE). Clinical symptoms include headache, altered mental status, and seizures with focal neurological signs.

The medial temporal lobe is most commonly affected; therefore, status epilepticus and retrograde amnesia are the hallmarks of this disease. MRI showed symmetrical hyperintensity in the medial temporal lobe, with decreased metabolism on PET scan. Testing to distinguish primary HHV6 infection from reactivation remains a challenge. The literature has suggested plasma or blood viral load monitoring in conjunction with PCR determination of HHV6 DNA in CSF.

These test results in the above clinical setting with supportive MRI findings are fundamental to the diagnosis. In rare cases, a brain biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

There is no licensed therapy for HHV6 infection. Several treatment strategies appear to be reasonable based on case reports, including ganciclovir, foscarnet, cidofovir, and brincidofovir.

It is important to note that reports of HHV6 resistance to ganciclovir are increasing. In these cases, foscarnet may be the next drug to be considered for HHV6 encephalitis.

Human herpes virus infection can cause significant neurological morbidity and mortality. Rapid recognition, diagnosis, and treatment are essential. Knowledge of advanced tests and characteristic imaging lesions for each virus will help to achieve an accurate and timely diagnosis. Neurologists need to be knowledgeable about herpesvirus drug resistance patterns and alternative treatment regimens to ensure that patients receive appropriate treatment.

Although infection with EBV, CMV and HHV6 is predominantly seen in immunocompromised individuals, they can still cause infection in healthy individuals. Clinicians need a low threshold of suspicion, in the appropriate clinical setting, to initiate antiretroviral therapy and perform advanced CSF and neuroimaging tests.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.

Articles source references:

Baldwin KJ, Cummings CL. Herpesvirus Infections of the Nervous System. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2018;24(5, Neuroinfectious Disease):1349-1369.