This is an automatically translated article.

Localized sclerosis is more common in children and less severe than systemic sclerosis, but can cause joint and growth problems. There is no cure, some methods only help control symptoms and reduce the risk of complications.

1. Overview of localized scleroderma

Autoimmune scleroderma generally has the English name "Scleroderma" - meaning hard skin. Localized scleroderma affects the tissues underneath the skin, including muscles and bones. In addition to the hardening of the skin, the disease also changes the color and texture of the skin, making it impossible for the underlying tissues to develop normally. Localized scleroderma usually has two main types, including:

Banded scleroderma: Lesions have the form of long lines or streaks, almost like a knife scar; Focal scleroderma: Lesions appear as circular waxy patches. Most patients only have localized scleroderma on one part or one side of the body. Initially, some patches of skin will be red or purple, with a clearly visible borderline. Others may present with white, waxy patches of skin that grow hard and thicken.

2. Who can get localized sclerosis?

Localized scleroderma occurs in all ages and races, but is more common in Caucasians. Most patients with autoimmune scleroderma are female. Environmental factors may play a role, but are not the direct cause of the disease. Those risks include:

Injury; Infection ; Exposure to drugs or chemicals.

Tiếp xúc với thuốc hoặc hóa chất có thể làm gia tăng nguy cơ rủi ro

Autoimmune scleroderma is not contagious, so it will not spread in any way. The disease is also not passed from parent to child, although certain genes can make a child more likely to develop localized scleroderma.

Localized sclerosis is a rare disease, with an estimated number of patients worldwide. According to one statistic, 50 out of every 100,000 children will have localized scleroderma.

Most children with localized sclerosis do not have to change too much in their lifestyle, should still go to school as usual. If the child has a serious illness that affects the ability to walk or write, they should be educated in separate centers. Parents should encourage their child to stay active, with the exception of some high-impact sports activities.

3. Causes and diagnosis

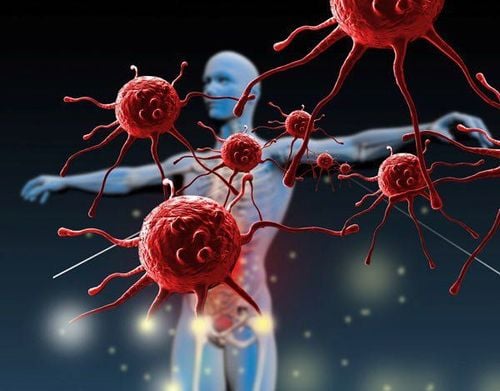

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disease in which the patient's own immune system causes them to develop skin inflammation. Inflammation activates connective tissue cells, causing them to overproduce collagen, a fibrous protein that plays a key role in many body tissues. Excess collagen can lead to fibrosis, which causes a scar-like appearance.

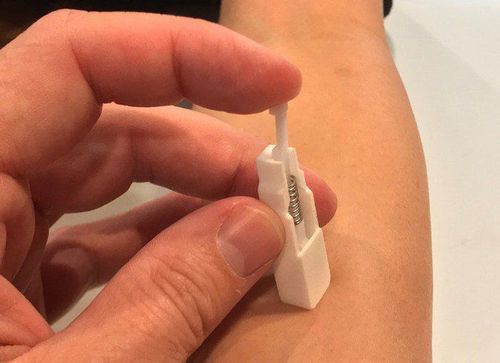

Based on the patient's medical history and physical examination, scleroderma is usually diagnosed by a rheumatologist or dermatologist. There are no specific criteria for diagnosing localized scleroderma, but tests are often done to assess inflammation and related problems. Thanks to that, the doctor can make a differential diagnosis, ensuring that the patient does not have other autoimmune diseases. A skin biopsy is also often done to confirm the diagnosis.

Sinh thiết da giúp các bác sĩ chẩn đoán bệnh xơ cứng bì cục bộ

4. Scleroderma treatment

The treatment regimen is designed depending on the patient's condition, the location and extent of the lesion, as well as other related issues. Of these, careful clinical assessment is the main method for monitoring scleroderma. Current treatments focus on controlling inflammation, which helps reduce the risk of serious problems.

4.1. Drugs that suppress the immune system Patients with scleroderma, head lesions, deep or widespread, are often treated with immunosuppressive drugs. However, the drug can increase the risk of infection and other side effects, so it should be prescribed by a doctor. These drugs include:

Methotrexate : Injected or taken once a week; Oral corticosteroids (prednisone); Intravenous infusion of methylprednisolone; Others: Mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine and tacrolimus. A clinical trial showed that methotrexate was superior to placebo in disease control after initial corticosteroid therapy. However, more research is still needed to determine the best therapy for localized scleroderma.

4.2. Anti-inflammatory and softening medications For people with milder forms of the disease, topical medications can be used to control inflammation and soften the skin. These medications include corticosteroids, calcipotriene, tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, and imiquimod, as well as moisturizers.

Sử dụng thuốc bôi giúp người bệnh kiểm soát tình trạng viêm và làm mềm da

4.3. Phototherapy Phototherapy, including both UVB and UVA rays, has been used to treat widespread skin disease. But more research is needed to assess the potential side effects of exposing pediatric patients to large amounts of UV light.

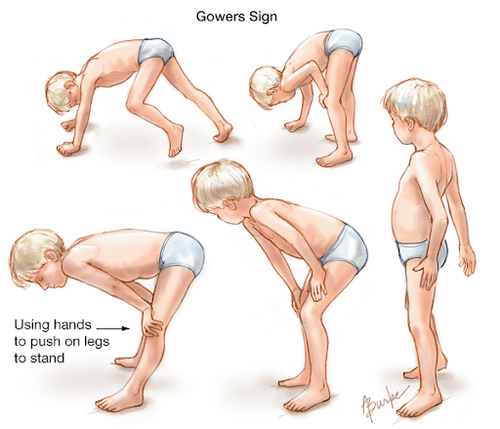

4.4. Physiotherapy Physical therapy and rehabilitation help improve strength for patients with muscle weakness, limb length disparities, and limited joint mobility. Early treatment can prevent sclerosis.

4.5. Surgery Surgery is not usually recommended in the treatment of autoimmune scleroderma. This method is only necessary for patients who have severe pain, greatly affect life function, or improve aesthetics for people with severe facial lesions.

However, the already damaged skin will be difficult to recover after surgery. In some cases, surgery even triggers a new flare-up. Therefore, for skin lesions that are not too obvious or prominent, the patient can use makeup to overcome defects.

In general, there is no cure for localized scleroderma. The disease may clear up on its own, or go into remission, over time. The plaque-like lesions of focal scleroderma do not spread and penetrate deeper into the subcutaneous tissues after several years. However, banded sclerosis - especially of the scalp - can persist for many years. Therefore, patients still need to continue to be monitored at least once a year, even after stopping treatment, because the disease may recur.

Người bệnh xơ cứng bì khu trú cần tái khám định kỳ theo lịch hẹn của bác sĩ điều trị

5. Complications

The prognosis for patients with partial scleroderma is better than that of generalized scleroderma. While it doesn't affect internal organs or be life-threatening, it can deform and harden the skin, causing discomfort, sores, and limited range of motion in the joints.

People with scleroderma are at risk for growth problems, such as a deformed limb (growing shorter or smaller), or deformity of part of the face or scalp. Children with band sclerosis on the face or head may experience eye inflammation, problems with their eyelids or teeth, headaches, seizures, and brain damage. Patients need regular eye exams, as well as brain and eye MRI for evaluation.

Other complications include: arthritis, limited range of motion, muscle atrophy, and gastroesophageal reflux... Children with localized ingrained scleroderma are at increased risk for chronic skin ulcers and carcinomas squamous cell tissue.

In summary, treatment of autoimmune scleroderma should generally be initiated as soon as possible. Drugs in the inflammatory phase that do not directly target fibrosis are more effective. Patients need regular follow-up with a rheumatologist to control inflammation and reduce drug-induced side effects. In particular, children with the disease should see a pediatric rheumatologist at least once a year because banded scleroderma can persist for years, or recur after a period of inactivity.

For detailed advice, please come directly to Vinmec health system or register online HERE.

Reference source: webmd.com; rheumatology.org