This is an automatically translated article.

Posted by Doctor Mai Vien Phuong - Department of Medical Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Central Park International General Hospital.

In this review, the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and presentation of most common esophageal motility disorders (EMD) will be covered. Achalasia is the best described disorder in the group and its features will be highlighted. As diagnostic and therapeutic options for esophageal motility disorders are increasing, a multimodal approach is required and referral to gastroenterology or surgery is recommended for further management of these disorders.

Esophageal motility disorders (EMD) represent a diverse group of conditions that alter the normal motility and movement of food from the esophagus into the stomach. The most common symptoms include difficulty swallowing and chest pain. Difficult to distinguish from other common diseases such as coronary artery disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease and malignancy. Standard evaluation included upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, barium esophagography, and esophageal manometry. The most well-described and most complete esophageal motility disorder is achalasia, which causes increased esophageal motility and poor relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (lower esophageal sphincter). Treatment for achalasia focuses on reducing the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter to allow gravity to allow food to pass through the stomach. Balloon dilation and laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) with angioplasty are standard treatments for achalasia.

1. Introduction

The esophagus acts as a tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach. The upper and lower esophageal sphincters, located at the proximal and distal ends of the esophagus, regulate the movement of food in and out of the esophagus. Under normal circumstances, swallowing occurs in a coordinated, sequential fashion using the muscles of the esophageal wall. This process is called esophageal peristalsis. The lower esophageal sphincter maintains basal tone to prevent gastroesophageal reflux disease. When peristalsis pushes food to the lower esophageal sphincter, this muscle relaxes to allow food to enter the stomach before re-establishing its basal tone. Esophageal motility disorders (EMDs) are rare disorders of esophageal and lower esophageal sphincter motility. Although sometimes asymptomatic, they are often characterized by dysphagia, chest pain, regurgitation, and, if severe, can manifest as weight loss, aspiration pneumonia, and malnutrition. Primary esophageal motility disorders are not associated with systemic diseases while secondary motility disorders are associated with a systemic disease such as scleroderma or malignancy.

In this review, the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and presentation of most common esophageal motility disorders will be covered. Achalasia is the best described disorder in the group and its features will be highlighted. Prophylaxis for these conditions includes upper endoscopy, barium contrast esophagography, and high-resolution esophagometry. Management including the role of medications, injections, balloon dilation, surgery, and new endoscopic treatments will be addressed. As the diagnostic and therapeutic options for esophageal motility disorders are increasing, a multimodal approach is required and referral to gastroenterology or surgery is recommended for further management of these disorders.

2. Epidemiology

Esophageal motility disorders are rare. Achalasia, the best-characterized disorder in this group, occurs in 1-2 people per 100,000 population. More common disorders include esophageal spasm or inefficient motility disorders and are poorly described and described. There is some recent data to suggest that these disorders - in particular achalasia - may be increasing in incidence. However, this is most likely due to the increased use of high-resolution esophageal manometry to improve the characterization and diagnosis of these conditions. Due to the rarity of these disorders, demographic information is not well understood. Achalasia occurs most commonly during the 4th and 5th decades, however it can occur in children and in patients over 90 years of age.

3. Pathogenesis

Esophageal motility disorder is a disorder of the muscle lining the esophagus. In achalasia, the neurons of the myocardium are destroyed by chronic inflammation leading to esophageal motility disorders and poor dilation of the lower esophageal sphincter. The cause of chronic inflammation is unknown but could be an infectious agent in a genetically susceptible person.

In South America, an achalasia-like disorder known as Chaga disease is caused by infection with the protozoan T. cruzi bacteria. Similar to idiopathic achalasia, this disorder causes inflammation of the esophageal plexus with consequent disturbances in esophageal motility and non-dilation of the lower esophageal sphincter (lower esophageal sphincter). However, patients with spastic esophagitis have a normal myocardium. The etiology of these motility disturbances may be due to fragmentation of vagus and mitochondrial nerve endings, esophageal muscle hypertrophy, and anxiety.

4. Clinical manifestations

The classic presenting symptom of achalasia is difficulty swallowing larger solids than liquids, often occurring for many years before being diagnosed. Patients often learn to adapt to dysphagia by changing their diet or performing exercises that improve swallowing. Dysphagia is often accompanied by easy regurgitation of poorly digested food or liquids and is often worse in the supine position or after eating several meals. Sometimes regurgitation can lead to aspiration pneumonia. With poor nutrition, weight loss is inevitable. Patients with low back pain or spastic dyskinesia may complain of chest pain, which may or may not be worse with swallowing. Chest pain is often incorrectly identified as being due to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is rare in patients with lower esophageal sphincter pressure.

5. Differential diagnosis

When middle-aged patients report chest pain as part of their symptom complex, coronary artery disease and GERD must be considered initially. It is difficult to distinguish movement disorders from coronary artery disease, especially in patients who may have other risk factors for coronary artery disease such as diabetes, hypertension, tobacco use, or family history. However, chest pain associated with esophageal motility disorders is often associated with food intake and is often sharp, non-radiating, and rarely lasts more than a few minutes. This is in contrast to angina pectoris which is often associated with exercise and exertion and is a persistent, dull, or severe chest pain that may radiate to the jaw or left arm.

Patients with esophageal motility disorders are often incorrectly diagnosed with GERD and receive antisecretory therapy with H2-receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors. These medications often fail to provide benefit for reported symptoms, which may be the first clue that acid reflux is not a contributing factor to the patient's illness. Patients with lower esophageal sphincter (i.e., low back pain) hypertension have reflux rather than GERD and a careful history can often distinguish between the two symptoms. Reflux is the easy return of liquid or poorly digested food from the esophagus up near the upper esophagus or mouth. The ingredients do not have gastric acid, so there is usually no report or sensation of heat. Reflux esophagitis, on the other hand, requires a relaxed or discontinuous lower esophageal sphincter. Movement of gastric contents into the esophagus is often accompanied by a burning sensation in the chest or mouth and is usually well controlled with the addition of an H2 blocker or PPI.

Dysphagia and weight loss are common symptoms of achalasia but are also primary malignancies of the esophageal or gastroesophageal junction. Gastroesophageal junction malignancy can cause rapid weight loss and difficulty swallowing and is called pseudo-achalasia. These symptoms may also be seen in esophageal stricture, esophagitis, esophageal ulceration, or extrinsic compression from mediastinal masses.

6. Diagnostic procedures

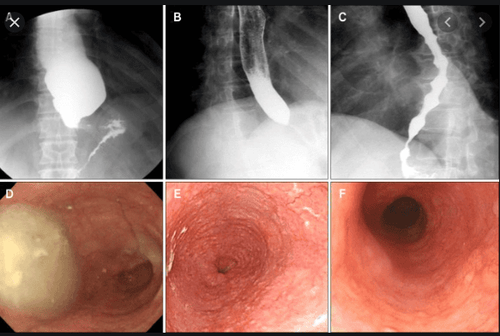

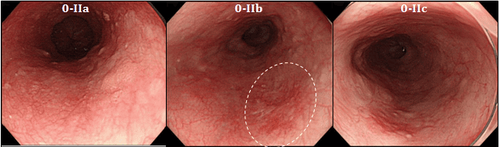

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (EGD) and contrast esophagography are often the first tests performed in patients with suspected achalasia or esophageal motility disorders. Patients with achalasia have a non-peristaltic (atony) esophagus that may become dilated with fluid or food trapped. Increased tone of the lower esophageal sphincter makes it difficult for oral or endoscopic contrast agents to enter the stomach. Baryt imaging often produces the classic "bird beak" appearance at the gastroesophageal junction.

Other motility disorders such as esophageal spasm or jackhammer's esophagus often represent random, chaotic esophageal spasms seen on endoscopy or esophageal x-ray.

The most important test for diagnosing esophageal motility disorders is high-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM). This test requires inserting a soft flexible catheter through the nose and into the upper part of the stomach. The catheter has a pressure sensor every 1-2 cm. In a high-resolution esophageal manometry, the patient is asked to swallow approximately 10 liquid swallows. Machine software generates maps showing time, length, and pressure that are used to further classify these disorders. The most commonly used classification system is called the Chicago Classification 3.0. In this classification, esophageal outlet obstruction (EGJ) is defined as having an elevated integrated dilatation pressure (IRP) at the lower esophageal sphincter and includes three subtypes of outlet obstruction and obstruction. EGJ output line congestion (EGJOO). The main peristaltic disorders have normal IRP and are termed dysmotility, distal esophageal spasm, and hypercontractile esophagus (Jackhammer). Minor disturbances include inefficient esophageal motility or fragmented peristalsis.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.