This is an automatically translated article.

Limited at the top by the diaphragm and extending below into the pelvis, the abdominal cavity contains most of the organs of the digestive system and parts of the genitourinary system. Abdominal blood vessels supply blood to various organs and tissue layers. Accordingly, the abdominal vascular anatomy is one of the most complex vascular systems in the body. An understanding of abdominal vascular anatomy is important for understanding clinical and surgical pathology.

1. Structure and function of abdominal vascular anatomy

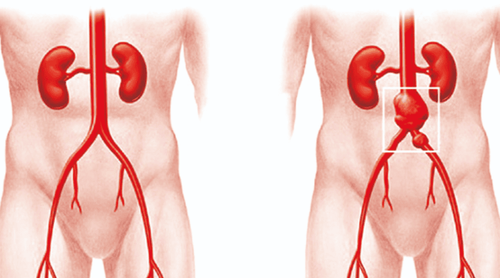

The blood supply to the abdomen is by branches of the abdominal aortic anatomy. The abdominal aorta is the continuation of the thoracic aorta into the abdominal cavity by penetrating the diaphragm close to the twelfth thoracic vertebra. The abdominal aorta bisects around the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae, providing an extensive network of branches for the abdomen and posterior branches for the pelvis and lower extremities.

Venous drainage of the abdomen is by the inferior vena cava and its branches. Blood from the portal vein passes through the liver and eventually flows into the inferior vena cava. The inferior vena cava originates at the fifth lumbar vertebra by connecting the left side with the right common iliac veins. It travels anteriorly to the spine, just to the abdominal aorta, then through the diaphragm at the eighth thoracic vertebra just before emptying into the right atrium in the ribcage.

2. Abdominal artery anatomy

The abdominal arteries arise from the anatomy of the abdominal aorta, enter the abdomen through the aortic foramen of the diaphragm near the T12 vertebra, and descend, on the left, to the inferior vena cava and anterior to the vertebral body. Before bifurcation at the L4 vertebra, the aorta supplies the renal arteries and the three main trunks supply the feeding organs.

The branches of the abdominal aorta include three main trunks, the visceral trunk artery, the superior mesenteric artery, and the inferior mesenteric artery, six paired branches, and a medial sacral artery.

All of the above arteries are streamlined to supply sufficient blood to the vascular-rich organs in the abdomen. Three major abdominal artery openings exist. The first is the hole between the splanchnic and superior mesenteric arteries through the pancreaticoduodenal arteries. The second is a hole that exists between the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries through the middle and left abdominal arteries. The third is an anastomosis between the inferior mesenteric artery and the internal iliac artery through the superior and middle or inferior rectal arteries.

When approaching the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra, the abdominal aorta bifurcates into the right and left common iliac arteries. From there, each common iliac artery runs laterally and further divides into the external and internal iliac arteries on each side. The external iliac artery then descends into the iliac fossa and becomes the femoral artery behind the inguinal ligament. The internal iliac artery is the main blood supply to the pelvis.

The anterolateral abdominal wall has a complex arterial supply. The major arteries are the superior epigastrium and branches of the muscular vessels, followed by the deep omental and lower epigastric vessels coming from the external iliac arteries. Next, are the superficial ectodermal and epigastric arteries arising from the femoral artery and the great omentum. Finally, the posterior intercostal arteries and branches of the subcostal arteries. The arteries of the anterior abdominal wall are arranged in circumference, like the intercostal arteries.

On the other hand, the arteries of the central abdominal wall are oriented longitudinally. The superior epigastric artery is an extension of the internal thoracic artery, which supplies the upper part of the rectum and connects to the inferior epigastric artery at the level of the umbilicus. The inferior epigastric artery arises from the external iliac artery. The deep ring artery also arises from the external iliac artery and supplies the ileal muscle. The femoral artery has two branches, namely the external iliac artery supplying the superficial abdominal wall in the inguinal region and the superficial epigastric artery supplying the superficial abdominal wall in the pubic region.

3. Anatomy of abdominal veins

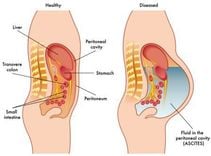

The inferior vena cava is the drainage system for the entire abdominal venous system, formed by the continuation of the two common iliac veins at the L5 vertebra. All substances from the upper abdominal viscera pass through the liver from the portal vein and into the liver. From the hepatic sinus, venous blood drains into the hepatic vein, then empties into the inferior vena cava and empties into the right atrium to be supplied with oxygen.

The portal vein drains all the veins from the abdominal part of the gastrointestinal tract except the lower part of the rectum and the anal canal. It also drains veins from the spleen, pancreas, and gallbladder. The portal vein is 8 cm long and is formed posterior to the pancreatic neck at the level of the L2 vertebra by the union of the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein. This is the main vein that supplies blood specifically to the liver with full nutrients absorbed from the lysis channel for metabolism. Its tributaries include the superior mesenteric vein, the splenic vein, the right gastric vein, the left gastric vein, the cystic vein, the paraumbilical vein, and the superior pancreaticoduodenal vein. The branches of the portal vein connect seamlessly with the branches of the inferior vena cava at various locations in the body, and these locations are called portal anastomosis. These sites are clinically relevant and are located at the lower end of the esophagus, in the liver, at the navel, at the end of the rectum, and in the anal canal.

The flow of the pelvic veins is formed by the confluence of adjacent veins in the pelvis. The various plexuses drain mainly into the internal iliac vein with some draining into the superior rectal vein and to the hepatic portal system. Another minor route to venous drainage for women is the ovarian vein. The superior gluteal veins are the largest branches of the internal iliac veins.

4. Physiological variations in abdominal vascular anatomy

A common variation occurring in 20% of the population in abdominal vascular anatomy is the presence of an accessory artery arising from the inferior epigastric artery and descending into the pelvis along the gland of the pubic branch. Another rare variant of the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery, the superior adrenal gland, and the inferior adrenal artery as a common trunk from the right renal artery.

There is a vascular variant of the anastomosis between the inferior epigastric artery and the obturator vessel in the obturator duct. Another variation involves the accessory obturator artery arising from the external iliac artery and forming a connection with the obturator artery exiting the internal iliac artery.

Such knowledge about variations of abdominal vascular anatomy is quite important in pathological diagnostic procedures and surgical interventions.

5. Diseases related to abdominal blood vessels

The abdominal and pelvic vascular system contains a multitude of arteries and veins that require special attention during surgery. Some examples include trauma to the abdomen and pelvis, injury to the ureters during pelvic surgery, or malignant metastatic glands.

Inferior epigastric artery may be injured by incision of the lower abdominal wall. The placement of trocars during laparoscopic surgery can also lead to intra-abdominal vascular injury. When these occur, a hematoma in the abdominal wall arises and can expand to a considerable size because the abdominal blood vessels have very poor tissue resistance in the local area.

During cesarean section and hysterectomy, the surgeon can injure the uterine artery or remove it when the incision breaks the broad ligament. In this situation, the trauma also runs the risk of getting into the suture when trying to stop bleeding because the ureter is close to the uterine artery.

Another surgical consideration for abdominal vasculature is that during hernia repair, the surgeon should be aware of a common variant of an abnormal obturator or accessory artery. This variant usually runs along the same route as the pubic branch of the obturator artery and can be damaged during surgery.

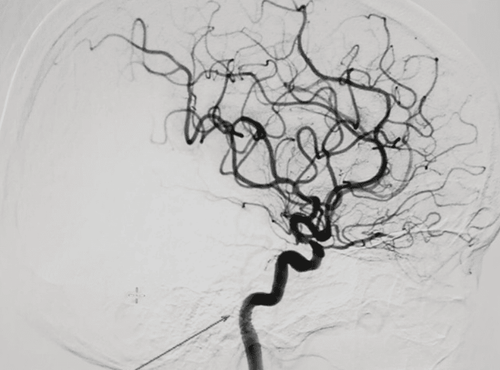

The lateral sacral veins connect with the internal vertebral venous plexus and act as an alternative route to the vena cava; This becomes important as a route of metastatic spread of prostate or ovarian cancer to vertebral or craniocerebral sites.

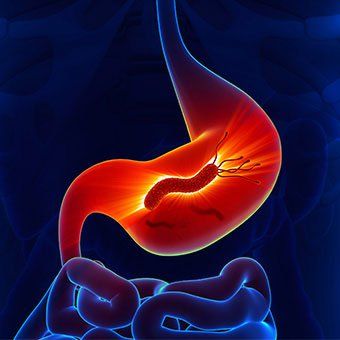

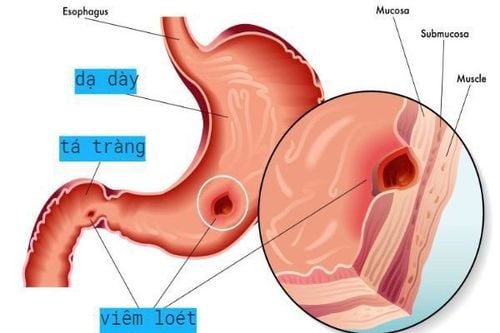

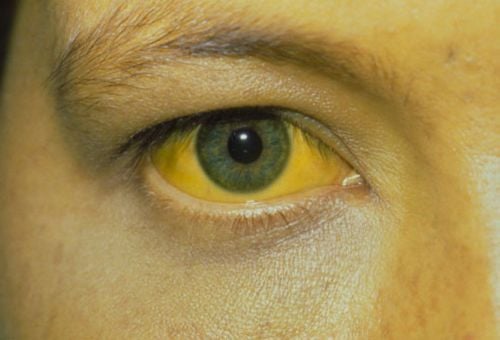

Bleeding from esophageal varices is a common complication of cirrhosis due to portal hypertension. This condition leads to severe bleeding at the anastomosis at the lower end of the esophagus. Other important locations of the stoma are at the lower end of the rectum and anal canal, where structural changes lead to hemorrhoids.

In summary, because the abdomen and pelvis contain most of the internal organs, these areas need to be supported by an extensive network of abdominal vascular anatomy. All arterial blood supplied to this area passes through the anatomical branches of the abdominal aorta and all venous blood eventually returns to the inferior vena cava. The organs and blood vessels of the abdomen can be affected by a variety of disease processes, including inflammation, infection, cancer, autoimmune, trauma, and degeneration. Whatever the condition, as these conditions can be treated with medication or surgery, ensuring an adequate blood supply to the affected area based on an understanding of abdominal vascular anatomy is critical. important for prognosis.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.