This is an automatically translated article.

Post by Master, Doctor Mai Vien Phuong - Gastrointestinal Endoscopy - Department of Medical Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Central Park International General Hospital.

Medium-chain triglycerides are lipid molecules that are more readily absorbed and oxidized than most lipids. This unique property of medium-chain fats has an important role in the treatment of a number of digestive disorders, especially fat malabsorption, and in optimizing nutritional status.

1. Structure of medium chain triglycerides

A fatty acid is a simple lipid molecule with a carboxylic acid group at one end and a hydrocarbon chain at the other end. Triglycerides are lipid molecules with three fatty acids attached to a glycerol backbone. Similar to simple fatty acids, the length of the fatty acid group determines the nomenclature of short-chain triglycerides (SCTs), medium-chain triglycerides (medium-chain fats) and medium-chain triglycerides. long (LCT).

The presence of double bonds can vary in fatty acids. Saturated fatty acids do not contain any double bonds along the hydrocarbon chain, while unsaturated fatty acids do. Monounsaturated fatty acids contain a single double bond, while polyunsaturated fatty acids contain two or more double bonds. Most fatty acids can be synthesized endogenously, with the exception of two long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids: linoleic acid and linolenic acid; They are considered essential fatty acids (EFAs) and must be obtained from the diet.

The fatty acid groups of medium chain fats include caproic acid, caprylic acid, capric acid and lauric acid. Compared with long-chain triglycerides, medium-chain fats have a smaller molecular mass, are water-soluble, oxidize quickly for energy, have a lower smoke point (the temperature at which volatile substances are produces and blue smoke is seen as a result of oil oxidation) and liquid at room temperature. Medium-chain fats contain only saturated fatty acids and are therefore free of EFAs, linoleic acid, and linolenic acid. Since medium-chain fats do not contain EFAs, they also do not serve as precursors to eicosanoid synthesis. Medium-chain fats provide fewer calories per gram than long-chain triglycerides, 8.3 versus 9.2, respectively.

2. Digestion and absorption

The length of fatty acids affects digestion and absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. The entry of triglycerides as long-chain triglycerides from the stomach into the duodenum stimulates intestinal secretion of the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) and pancreatic enzymes from the pancreas. CCK promotes the release of bile from the gallbladder to help emulsify triglycerides into smaller fat droplets to maximize its digestion. The pancreatic lipase then cleaves the fatty acid chains from the triglycerides to form individual fatty acid molecules, which then aggregate into micelles. The microspheres are absorbed into enterocytes along the intestinal contour via passive diffusion or transported by fatty acid transporters. Once inside the enterocytes, the fatty acids are transported into the endoplasmic reticulum.

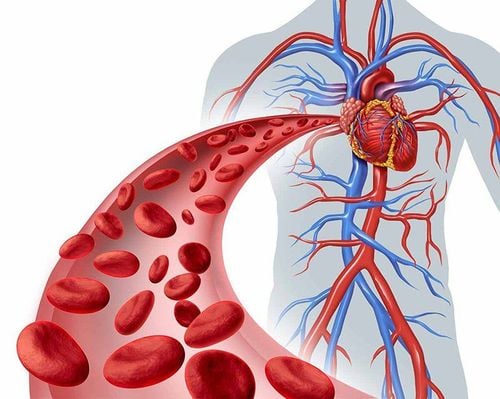

The chylomicrons are released through exocytosis, enter and move through the lymphatic system and finally, exit into the subclavian vein to reach the bloodstream. In the intracellular space, long-chain fatty acids bind to carnitine for transport into the mitochondria for subsequent B-oxidation. In states of carnitine deficiency that contribute to severe protein malnutrition (eg, chronic malabsorption, small bowel obstruction, starvation), these long-chain fatty acids cannot be used effectively and instead leads to accumulation of unoxidized fatty acids, impaired urea formation, ketosis as well as gluconeogenesis. Clinical sequelae may include fatty liver, hepatomegaly, myopathy, and altered mental status.

In contrast, the digestion of medium chain fats is quick and simple. Medium-chain fats do not stimulate CCK secretion. Absorption of medium-chain fats occurs via passive diffusion along the gastrointestinal tract into the albumin-binding portal system. No further encapsulation or modification of medium chain fat molecules is required. Furthermore, medium chain fats are not dependent on the carnitine acyltransferase system for transport into the mitochondria for B oxidation. This results in faster metabolism of medium chain fats and improved utilization of even in protein deficiency.

3. Medium chain fat sources

Most fats and oils of animal and vegetable origin contain long-chain triglycerides (e.g. fish, avocados, nuts, seeds, corn, peanuts, safflower and soybean oils) . In contrast, natural sources of medium-chain fats include coconut oil and palm kernel oil, although these oils also contain long-chain triglycerides. Commercial medium-chain fat formulations may include naturally derived medium-chain fat oils; 100% synthetic medium-chain fatty acids (produced from hydrolyzed medium-chain fatty acids from coconut or palm kernel oil, refined and then re-esterified to a glycerol backbone); physical blends (mixture of medium-chain fats and long-chain triglycerides) or structured lipids. Structural lipids are synthetic lipid molecules with a blend of medium- and/or long-chain fatty acids attached to the glycerol backbone. In a clinical setting, it is not uncommon for healthcare professionals to advise their patients to use coconut oil for medium-chain fats. However, depending on the case, this can exacerbate fat malabsorption due to the long-chain triglyceride content. Semi-element and elemental enteric formulations often include medium-chain fats to minimize the need for pre-digestion, although long-chain triglycerides may also be included as a source of EFAs. Possible clinical applications include malabsorption disorders due to pancreatic insufficiency or severe small bowel disease.

4. Dosage put into the body

Taking too much medium-chain triglyceride oil by mouth has been linked to gastrointestinal distress, such as abdominal discomfort, cramps, bloating, gas, and diarrhea. One tablespoon (15 mL) of medium-chain fat oil contains 14 grams of fat and 115 calories. A maximum daily dose of 50-100 grams has been suggested to improve gastrointestinal tolerance; this equates to 4-7 tablespoons (60-100 mL) per day (56-98 grams of fat and 460-805 calories).

The daily dose of medium-chain fats should be increased as tolerated to the maximum daily dose, with equally divided doses over all meals. Medium-chain fats can be easily mixed into a variety of foods and beverages. If medium-chain fats are used in cooking, the temperature must be kept below 150°C (302°F) to reduce the risk of oxidation, otherwise the flavor of the food may be affected.

One tablespoon of medium-chain fatty oil can also be administered through the syringe feeder along with a 30 ml water rinse before and after administration. In patients with severe fat restriction, a source of EFAs will need to be provided in the diet along with medium-chain fat supplementation to prevent EFA deficiency. Medium-chain fatty oils do not require a prescription. Although medium-chain fat has distinct characteristics, it is not considered a panacea and its use is purported to be used in conjunction with other therapies to treat the disorder.

5. Use of short-chain fats in gastrointestinal pathogenesis

Pancreatic insufficiency Pancreatic insufficiency is characterized by disruption of the exocrine function of the pancreas, which can lead to decreased synthesis and/or release of pancreatic enzymes that normally aid in the digestion of nutrients in the small intestine , especially long-chain triglycerides in the diet. It can arise in acute or chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, and as a result of pancreatectomy. The main intervention for pancreatic insufficiency is pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy and sometimes acid suppression therapy.

At this time, there is limited research on the effects of oral medium-chain fatty oils in pancreatic insufficiency. However, since medium-chain fats do not require pancreatic enzymes for digestion, it is reasonable to consider them as an additional source of calories for these patients if needed.

In chronic pancreatitis, there is interest in using medium-chain triglycerides to help relieve postprandial pain. A small study of 8 chronic pancreatitis patients with adequate pancreatic enzymes found consumption of an elemental enteric formula containing medium-chain fats (69% total fat; 9.8 grams per can). ), at least 3 times daily for 10 weeks, and 20 grams of dietary fat per day, increased minimal serum CCK levels as well as significantly reduced postprandial abdominal pain.

A study of 17 children with cystic fibrosis found no difference in absorption rates between a macromolecular enteral formula (Isocal) with pancreatic enzyme replacement and an elemental enteric formula (Peptamen) containing medium chain fats with no enzyme substitution.

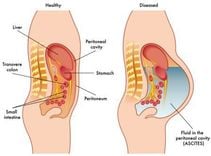

Chylous fistula is an opalescent or milky liquid consisting mainly of chylomicrons containing long-chain triglycerides and lymphatic fluid. Chyle originates in the small intestine, where chylomicrons are formed and absorbed into the lymphatic system via bacteria. Chyle then passes through the lymphatic system and enters the venous circulation through the thoracic duct. Obstruction or damage to the lymphatic system can lead to chylous fistulae into the pleural space, pericardium, or peritoneum. Common causes of chylous leakage include cancer, infection, radiation, and trauma.

Initially, nutritional management of chylous fistula may include fat restriction or no fat, elemental enteral nutrition with medium-chain fats, or a high-protein diet with added nutrients. medium chain fat.

These interventions should be used only for the short term (approximately 2 weeks), because there is a risk of developing EFA deficiency with long-chain triglyceride restriction in the diet for prolonged periods. Once the leak is closed, food can be gradually introduced into the diet. If chylous fistula persists despite these interventions, parenteral nutrition is indicated. With enteral nutrition, there is no need to restrict intravenous lipid emulsions, as they completely pass through the gastrointestinal tract and the lymphatic system.

Short bowel syndrome Short bowel syndrome is defined by a significant anatomical (or functional) reduction in the length of the small intestine, thereby resulting in impaired digestion and absorption of the small intestine. The significant malabsorption observed in these patients often manifests as diarrhea, unintentional weight loss, and fluid and electrolyte disturbances. The rationale behind the use of medium-chain triglycerides in short bowel syndrome is to provide efficiently absorbed calories with minimal need for prior digestion.

In summary, medium-chain fats have unique digestive, absorptive, and oxidative properties that should be used in gastrointestinal pathogenesis. The easy absorption of medium-chain triglycerides without the need for bile or pancreatic enzymes makes them a good source of calories in causing malabsorption and hyperlipidemia due to diseases, such as pancreatic or biliary insufficiency. Because of their ability to cross the lymphatic system, medium-chain fats may also serve as a lipid source for patients with chyme leak.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.

References:

Neha D. Shah, Berkeley N. Limketkai, The Use of Medium-Chain Triglycerides in Gastrointestinal Disorders, Nutrition issues in gastroenterology, series

160, practicalgastro. Bach AC, Babayan VK. Medium-chain triglycerides: an update. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36(5):950-62. 2. Gropper SS. Advanced nutrition and human metabolism. 6th Ed. ed. Belmont, OH: Cengage Learning; 2012.