This is an automatically translated article.

Posted by Master, Doctor Mai Vien Phuong - Head of Department of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy - Department of Medical Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Central Park International General Hospital.

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is a malabsorption condition. This syndrome is usually not clinically apparent if approximately three-quarters of the small bowel (SB) is not resected. Because of the broad short bowel length and the compensatory capacity for bowel resection, the definition of short bowel syndrome is not based on the length of the remaining bowel.

1. Etiology and epidemiology of short bowel syndrome

In adults, more common causes of short bowel syndrome include multiple resections for Crohn's disease, mass resections for mesenteric vascular events, and malignancies. Postoperative obstructive and vascular events requiring massive bowel resection appear to be increasing in incidence and in a recent series of diseases the most common cause of short bowel syndrome in humans big.

Notably, the operations leading to short bowel syndrome after open surgery appear to differ from those following laparoscopic methods, such as the most common gastric bypass and cholecystectomy or laparoscopic and colectomy, hysterectomy, appendectomy, etc. The main mechanisms responsible after open and laparoscopic surgery are postoperative adhesions and volvulus, respectively. Although advances in the treatment of Crohn's disease may lead to a reduction in short bowel syndrome, this improvement does not translate into a reduction in the need for parenteral nutrition at home (parenteral nutrition).

2. Frequency of short bowel syndrome in adults

The incidence and prevalence of short bowel syndrome is unknown because there are no reliable databases. Estimates are based on information from home registries, with short bowel syndrome being the most common indication. Two recent studies limited to patients with short bowel syndrome showed that the majority of patients were female and >50 years of age. In the United States, the annual rate of parenteral nutrition at home is estimated to be about 120 parts per million, of which about 25% have short bowel syndrome; this number reached about 10,000 adults in 1992. These numbers do not reflect short bowel syndrome patients who were able to wean from parenteral nutrition during the index hospital stay. or can successfully wean parenteral nutrition at home. Therefore, the incidence of short bowel syndrome may be underestimated.

3. Anatomy and related physiology

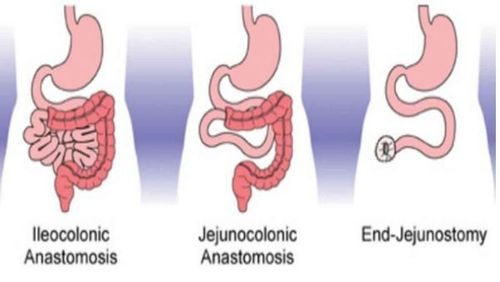

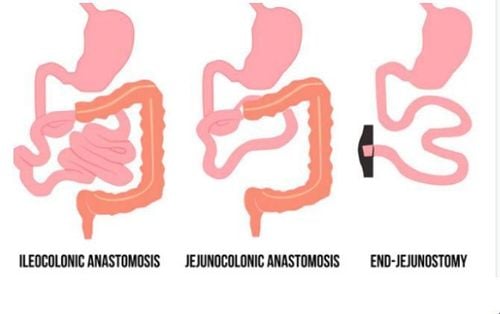

Three anastomosis may occur in short bowel syndrome and are often described in terms of the location of the anastomosis after resection:

The ileocolonic anastomosis. The mouth connects the jejunum and the ileum. Open the jejunum or ileum to the skin. The clinical manifestations and outcomes of short bowel syndrome vary depending on the remaining bowel anatomy and its residual function. Therefore, an appreciation of the bowel anatomy seen in short bowel syndrome along with basic considerations of gastrointestinal physiology is helpful to better understand prognosis and guide patient management.

4. Small intestine

The nearly 100 to 150 cm segment of the jejunum is the primary site of absorption of water-soluble carbohydrates, proteins and vitamins. Fat absorption can extend over a greater length of the short intestine if more fat is ingested. In a healthy adult, approximately 4l of intestinal secretions (0.5l of saliva; 2l of gastric acid and 1.5l of pancreatic secretions) are produced in response to food and drink consumed per day. . Water absorption is a passive process due to the active transport of nutrients and electrolytes. Sodium transport creates an electrochemical gradient that promotes absorption of nutrients across the intestinal epithelium. Because the junctions between the jejunal epithelial cells are significant compared to other areas of the intestine, a rapid outflow of fluid and nutrients occurs resulting in less efficient fluid absorption and isotonic jejunum contents. The absorption of sodium in the jejunum occurs along a concentration gradient. These factors become especially important in patients with jejunal-only short bowel syndrome.

In contrast to the jejunum, the ileum has tighter intercellular junctions resulting in less water and sodium. In the ileum, the active transport of sodium chloride allows significant fluid reabsorption and the ability to concentrate the contents. The distal ileum is also the primary site of carrier-mediated absorption of bile salts and B12. The ileum and proximal colon produce several hormones including glucagon-like peptides. 1 and 2 and peptide YY have functions to regulate transport/peristalsis (eg, jejunal and ileal braking) and bowel properties. The benefit of the ileal valve in slowing transit and preventing the reflux of large intestine contents into the small intestine is controversial as this benefit may reflect the retention of a significant length of the ileum. terminal ileum.

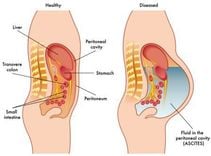

5. Colon

The colon has the slowest transit speed, the tightest intercellular junctions, and the highest water and sodium absorption efficiency. In terms of health, usually 1 to 1.5l/day of fluid enters the colon, where all but about 150 ml is reabsorbed. In short bowel syndrome, the colon plays an important role in fluid and electrolyte balance with its capacity to store and absorb up to 6l per day. Complete colonic loss often leads to fluid and electrolyte disturbances. In addition to colon repair, microbial fermentation of poorly absorbed carbohydrates into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) with subsequent colonic absorption provides 10-15% more energy requirements or up up to 1000 kcal per day. Thus, the colon becomes an important organ for absorbing fluids and electrolytes and for saving energy in short bowel syndrome.

6. Stomach and pancreas

Massive hysterectomy is associated with transient gastric hypersecretion and may persist for up to 12 months postoperatively. This may occur due to loss of inhibitory hormones produced in the proximal intestine (eg, gastric inhibitory peptide and enteric active peptide). This increases the volume and decreases the pH of secretions entering the proximal SBP, potentially exacerbating fluid loss and leading to gastrointestinal complications and impaired function of digestive enzymes, contributing to in addition to fat indigestion.

The use of antisecretory drugs including proton pump inhibitors or histamine 2 receptor antagonists reduces gastric secretion, prevents gastric complications, and may lead to improved digestion and absorption. Although some short bowel syndrome patients with extensive proximal SBP resection may lose the site of secrettin and cholecystokinin-pancreozymin (CCK-PZ) synthesis leading to decreased bile secretion, most have extensive distal SBP resection and demonstrate normal excretion of these substances. Resection of >100 cm of terminal ileum reduces bile acid reabsorption into the enteric circulation, leading to a decrease in bile salts, which ultimately exceeds the liver's full replacement synthesis capacity. This bile acid deficiency leads to impaired micelle formation and fat digestion, clinically manifesting as a deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins and increased lipolysis. In addition, the entry of caustic bile acids into the colon causes net secretion of fluid into the colon and accelerates peristalsis of the colon which increases stool volume.

7. Intestinal adaptation

Intestinal adaptation is the process by which, after intestinal resection, the remaining intestine undergoes micro and macro changes in response to internal as well as external stimuli to its absorptive capacity. be increased. Intestinal nutrients are important in promoting the adaptive response.

Adaptation will occur during the first two years after bowel resection. Depending on the extent and location of the intestine removed and the nutritional composition of the diet, adaptive structural and functional changes may occur. People who have had a terminal jejunal resection often have little or no adaptation, and the colon also undergoes adaptive changes after a large bowel resection.

8. Determine residual bowel anatomy and its effect on outcome

The large range of SB lengths from approximately 300 to 800 cm in adults emphasizes the importance of determining the length and length of the small intestine remaining after any resection. The length and area of residual SBP and the presence of even a partial colon are important factors influencing the outcome of patients with short bowel syndrome. Establishing an accurate estimate of bowel length is often difficult because surgical reports often record the amount of bowel removed rather than the amount remaining. SB length can also be estimated on a series of barium-enhanced SBs, which may also be useful for characterizing other structural features such as the presence of bowel dilatation.

Recently, computed tomography (CT) of the intestine with three-dimensional reconstruction and calculation of SB length has been shown to provide similar information. However, the importance of remaining small bowel length in determining clinical outcome in patients with short bowel syndrome. The ultimate determinant of short bowel syndrome severity and end result is the vital mass of functional absorptive epithelium of the remaining intestine.

Because of the difference in adaptability, people with ileal remnants have a better prognosis than those with only jejunal remnants. In adults, terminal ileostomy >60cm usually requires vitamin B12 replacement, whereas resection >100cm leads to disruption of intestinal circulation leading to bile salt deficiency and fat malabsorption. Extensive ileostomy also results in faster gastrointestinal transit, in part due to a reduction in the hormones that regulate bowel transit. The presence of a colon has been shown to be beneficial in short bowel syndrome due to its ability to absorb water, electrolytes and fatty acids, slow intestinal transit, and stimulate intestinal adaptation.

In summary, short bowel syndrome patients undergoing jejunostomy are generally the most difficult to manage and most likely to require permanent parenteral support.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.

References

John K. DiBaise, Carol Rees Parrish, Short Bowel Syndrome in Adults – Part 1 Physiological Alterations and Clinical Consequences, Nutrition issues in gastroenterology, series

132, Practical gastroenterology • august 2014. 1. O'Keefe SJ , Buchman AL, Fishbein TM, Jeejeebhoy KN, Jeppesen PB, Shaffer J. Short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure: consensus definitions and overview. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jan;4:6-10. Dabney A, Thompson J, DiBaise J, et al. Short bowel syndrome after trauma. Am J Surg 2004;188:792-795. 3. Amiot A, Messing B, Corcos O, Panis Y, Joly F. Determinants of home parenteral nutrition dependency and survival of 268 patients with non-malignant short bowel syndrome. Clin Nutr 2013;32:368-374. Thompson JS, DiBaise JK, Iyer KR, et al. Postoperative short bowel syndrome. J Am Coll Surg 2005;201:85-89

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.