This is an automatically translated article.

Post by Master, Doctor Mai Vien Phuong - Gastrointestinal endoscopy - Department of Medical Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Central Park International General Hospital.Pancreatic cancer or pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a deadly disease with a 5-year survival rate of about 6%. Accordingly, the oral or fecal microbiota could be a novel and potential diagnostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer.

1. Overview

Pancreatic cancer or pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a deadly disease with a 5-year survival rate of about 6%. Early detection and diagnosis are essential for effective surgical treatment to improve cancer survival, but this remains a major challenge. Many diagnostic methods are available.

For example, deoxyrib-onucleic acid (DNA) sequencing for the detection and diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is limited in clinical use due to the need for fresh, high-quality specimens, tumor content, and nature. tumor heterogeneity. Molecular markers, such as mutated DNA or DNA methylomes, also have limited clinical use to enhance diagnostic sensitivity or early detection of pancreatic cancer recurrence. The Ca19-9 biomarker is commonly used for the diagnosis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer with a diagnostic sensitivity of 0.78 and a specificity of 0.77, but this biomarker test has a sensitivity of 0.78 and a specificity of 0.77. limited in patients with jaundice, pancreatitis, enteritis, and hyperglycemia, as these patients often have elevated Ca19-9 levels. In addition, the 7%-10% Lewis (a-/b-) population was unable to express Ca19-9.

Trắc nghiệm: Bạn biết gì về các yếu tố nguy cơ, chẩn đoán và điều trị ung thư tuyến tụy?

Ung thư tuyến tụy phổ biến thứ 10 trong những bệnh ung thư mới và là nguyên nhân thứ 4 gây tử vong do ung thư ở nam, nữ. Bài trắc nghiệm này sẽ kiểm tra kiến thức của bạn về các yếu tố nguy cơ, chẩn đoán và cách điều trị ung thư tuyến tụy.

Bài viết tham khảo nguồn: medicalnewstoday 2019

2. Bacterial flora in the oral cavity

The oral cavity contains nearly 619 taxa in 13 phyla (Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chlamydiae, Chloroflexi, euryarchaeota, spirochaetes, SR1, Synergistes, Tenericutes, and TM7) and 68% of those phylotypes wild.

Advanced genome sequencing for the distribution of the human oral microbiome makes it possible to measure bacterial species ratios without relying on traditional culture methods. Saliva was found to contain a broad spectrum of bacteria with an easy and relatively cost-effective sampling method. Although there are few studies on oral flora and pancreatic cancer in humans, the impact of geographic and medical factors, such as race and ethnicity, different dietary habits, use of antibiotics and cancer, which can cause oral bacteria profiles to differ from person to person. from different geographical locations.

3. Oral or fecal microbiota could be a new and potential diagnostic biomarker

Oral or fecal microbiota profiles of gastrointestinal and colorectal cancers, oropharyngeal, liver and lung cancers may represent a novel and potential diagnostic biomarker. Studies have found that gastrointestinal and oral microbiota differ in abundance in pancreatic cancer patients compared with healthy individuals. Cancer risk is increased with transport of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, and Alloprevotella, while Fusobacterium, Leptotrichia, Neisseria elongate, and Streptococcus mitis may be protective factors for pancreatic cancer.

However, Olson et al did not find a significant difference in oral microbiota diversity between patients with pancreatic carcinoma (n = 40), intraductal papillary mucinous cell tumors (IPMN) (n = 39) and healthy (n = 58) participants in the United States. The conflicting findings in previous studies may be due to differences in methodological approaches and sample collection. For example, several studies have performed quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to confirm bacterial candidates, and some sequencing studies have performed microbiome profiles in tongue-coated samples. or mouthwash sample.

4. What does the research say?

A study was conducted in patients living in Sichuan province, southwestern China, enrolling 80 patients over 18 years of age and suspected of having pancreatic tumor prior to biopsy or surgery. Histopathological results confirmed 45 patients with primary pancreatic carcinoma and 35 patients with noncancerous pancreatic tumors, including 9 IPMNs, 11 pancreatic serous cysts, 5 solid pseudocysts. and 10 neuroendocrine tumors. The authors also recruited 69 healthy participants from the community as the comparison group. Healthy adults with normal liver and kidney function, normal heart-lung function, no history of cancer, and no viral infection. Participants were excluded if they had:

(1) History of malignancy and prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy; (2) Metastatic pancreatic carcinoma or pancreatic carcinoma with another cancer; (3) History of viral infection (ie hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus); (4) Use of antibiotics (including oral, intravenous, or intramuscular) and probiotics within 4 weeks prior to admission (5) Use of corticosteroids (nasal or inhaled) or immunosuppressants other.

5. Bacterial taxonomic change in pancreatic carcinoma

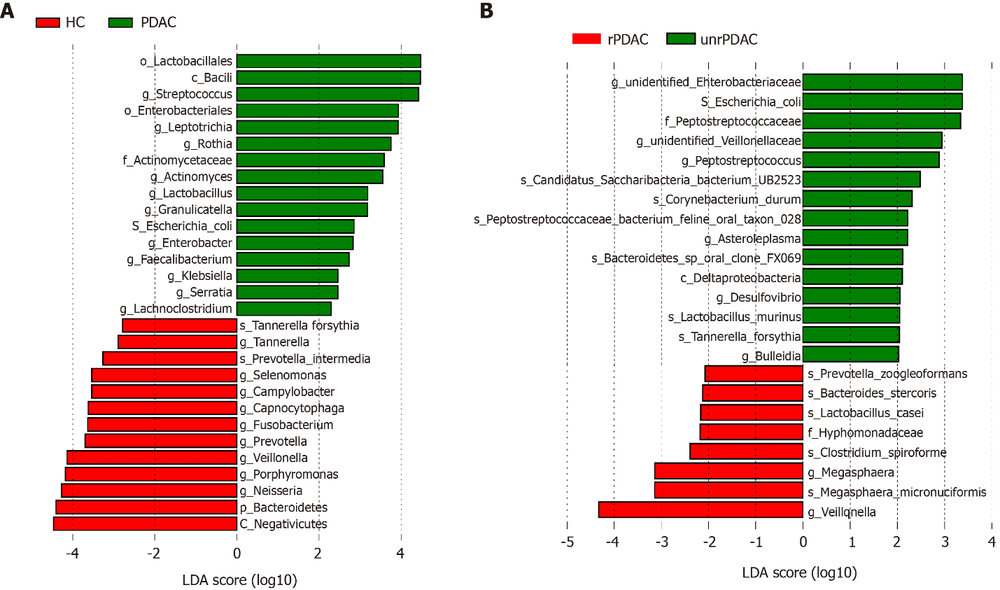

The authors used a linear discriminant analysis effect size algorithm to evaluate the bacterial taxonomic composition and differences between the pancreatic carcinoma group and healthy control subjects. Compared with the healthy group, pancreatic carcinoma patients were significantly enriched in the order_Lactobacillales, class_Bacilli, genus_ Streptococcus, phylum_Firmicutes, genus Actinomyces, genus Rothia, genus Leptotrichia, genus_ Lactobacillus, species_ Escherichia_coli, and order_Enterobactees (Fig. 2 A ). In contrast, pancreatic carcinoma patients had significantly reduced amounts of Selenomonas, Porphyromnas, Prevotella, Capnocytophaga, Alloprevotella, Tannerella and Neisseria at the genus level. The authors also compared the bacterial distribution between pancreatic carcinoma and pancreatic carcinoma patients. Figure 2B shows that species_ Escherichia coli, genus Peptostreptococcus, genus Asteroleplasma and species_ Tannerella forstythia were more common in the adenocarcinoma group, while the authors found the presence of species_ Bacteroides stercoris, genus_ Megasphaera and genus Veillonella

6. Oral microbiota dysbiosis exists in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma

This prospective study found that oral microbiota dysbiosis persisted in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Fecal microbiota is the primary sampling method for pancreatic cancer research. The authors' research uses the saliva sampling method, which is convenient and the sample quality is easy to control during the sampling process. When comparing the bacterial profile from the authors' saliva and stool samples from another study in Chinese pancreatic carcinoma patients. Accordingly, the gut microbiota and saliva always had a low Shannon index and a high Chao1 index, and Lactobacillus, Enterobacter and Leptotrichia at the genus level were significantly increased. This provides supporting evidence that salivary sampling produces similar bacterial structures compared with stool sampling, which is often difficult to collect. The authors' findings also provide additional evidence to confirm that Neisseria and Streptococcaceae are risk factors for pancreatic cancer.

7. Microbial richness and species diversity in pancreatic carcinoma patients

Regarding the microbial richness and species diversity, the authors' study showed that the pancreatic carcinoma group significantly increased the microbial abundance as estimated by the index Chao1 and ACE and reduced microbial diversity as estimated by the Shannon and Simpson index. Lu et al had similar findings from a study of Chinese pancreatic cancer patients using tongue coating samples. However, studies of non-Chinese populations did not find any difference in alpha diversity index of oral microbiota composition between pancreatic cancer patients and healthy individuals. The results of the study by the authors and Lu et al demonstrated that seven out of fourteen bacterial families (Leptotrichiaceae, Actinomycetaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Micrococcaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Moraxellaceae) were significantly increased and Porphyromonadaceae were significantly decreased. reported in Chinese pancreatic carcinoma patients. However, the authors' study found that the abundances of three of the fourteen bacterial families (Fusobacteriaceae, Campylobacteraceae, Spirochaetaceae) were significantly reduced in pancreatic carcinoma patients, whereas Lu and colleagues found significantly more richness. Both the authors' study and the study by Lu et al. found a significant increase in genera Leptotrichia, Actinomyces, Rothia, Rothia, Solobacterium, Peptostreptococcus and Oribacterium.

Torres et al found higher Leptotrichia and lower Porphyromonas in the saliva of pancreatic cancer patients, but found no significant difference in the expression of Streptococcus mitis and Granulicella adiacens. The conflicting findings between the authors' study and other studies may be due to different sample collection methods, e.g., salivary and tongue coating methods. Future research should compare different sample collection methods to study the microbiome. For example, saliva and tongue coating methods, focusing on the impact of geography, race, diet, antibiotic use (including consumption of antibiotic-containing meat products) , injury, disease, and hormonal shifts in flora analysis.

Saliva microbiota can differentiate pancreatic carcinoma from healthy individuals. A higher abundance of Streptococcus and Leptotrichia is associated with an increased risk of pancreatic carcinoma. Veillonella and Neisseria are protective factors for the detection of pancreatic carcinoma. Neisseria was recognized by all studies to reduce pancreatic cancer risk while Leptotrichia was identified in the authors' study as a potential pancreatic carcinoma predictor. Symptomatic patients have a different bacterial profile than asymptomatic patients. Because the symptoms of pancreatic carcinoma are often nonspecific, a combination of symptom assessment and microbiome can help with early detection of pancreatic cancer. Understanding the distribution of the microbiome is an essential step in developing probiotic treatment plans to reduce pancreatic cancer risk.

References Wei AL, Li M, Li GQ, Wang X, Hu WM, Li ZL, Yuan J, Liu HY, Zhou LL, Li K, Li A, Fu MR. Oral microbiome and pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(48): 7679-7692 [PMID: 33505144 DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i48.7679]

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.