This is an automatically translated article.

Posted by Master, Doctor Mai Vien Phuong - Gastrointestinal Endoscopy - Department of Medical Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Central Park International General Hospital

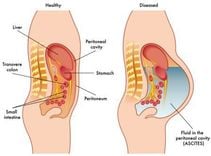

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is a malabsorption condition that is associated with a high frequency of complications. This syndrome usually does not become clinically apparent until about three-quarters of the small bowel (SB) has been resected.

Given the wide SB length and compensatory ability for bowel resection, the definition of short bowel syndrome should not be based solely on the length of the remaining bowel. Instead, experts in bowel failure have proposed to define short bowel syndrome as a condition resulting from surgical resection, congenital defect, or disease-related malabsorption, characterized by the inability to maintain a balance of protein, energy, fluids, electrolytes or micronutrients when the diet is normal. However, the presence of a residual small bowel <200 cm is often used to facilitate clinical diagnosis.

1. Intestinal adaptation

Intestinal adaptation is the process after intestinal resection whereby the remaining intestine undergoes macroscopic and microscopic changes in response to a variety of internal and external stimuli to increase absorption . Enteric nutrients are of particular importance in promoting an adaptive response, presumably by stimulating the pancreas to secrete, digest, and secrete gut hormones.

Adaptation is variable and usually occurs during the first two years after bowel resection in adults. Both adaptive structural and functional changes can occur depending on the extent and location of the gut removed and the nutritional composition of the diet. The ileum is both morphologically and functionally adaptive, while those with jejunostomy demonstrate a functional SB adaptation, and those with terminal jejunostomy show little or no adaptation. . The colon also seems to undergo adaptive changes after large bowel resection.

2. Complications of short bowel syndrome

A variety of disorders can further complicate the patient's course with short bowel syndrome. These complications may be due to pre-existing disease, altered bowel anatomy and physiology, or treatment modalities including parenteral nutrition and associated central venous catheters. Complications related to altered bowel anatomy are discussed below. Fluid, electrolyte, and micronutrient complications will be discussed in later articles in this series.

2.1 Oxalate nephropathy Chronic kidney disease and calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis can complicate the course of short bowel syndrome in individuals with colonic segmentation, sometimes leading to irreversible renal failure. Normally, dietary oxalates bind to calcium in the stomach and are excreted in the feces. In patients with short bowel syndrome who have persistent and fat malabsorption in the colon, calcium preferentially binds to unabsorbed fatty acids in the lumen so that oxalates freely enter the colon for absorption. blood, which is then filtered by the kidneys.

Decreased bacterial oxalate breakdown by reducing Oxalobacter-forming substances in the colon of patients with short bowel syndrome also contributes. Furthermore, citrate often blocks nucleation, the first step in kidney stone formation. Hypocalciuria is common in patients with malabsorption and is thought to be due to a loss of bicarbonate in the stool. In the kidney, oxalate binds to calcium leading to oxalate nephrolithiasis and the risk of progressive obstructive nephropathy. To reduce the risk of this complication, correcting dehydration is important while taking calcium citrate supplements, along with limiting fats and oxalate-containing foods. The clinical utility of the addition of Oxalobacter formigenes to increase the destruction of oxalates or cholestyramine, oxalate binding remains to be established. Urate nephrolithiasis is also relatively common in anostomy short bowel syndrome patients and is associated with chronic dehydration.

2.2 Metabolic bone disease Osteoporosis, osteoporosis, and secondary hyperparathyroidism may occur in patients with short bowel syndrome as a consequence of parenteral nutrition, altered intestinal anatomy causing malabsorption of nutrients. macro and micronutrients (especially vitamin D), medication use (eg, corticosteroids to treat an underlying disease), and other patient baseline factors such as gender, ethnicity, body size body and not enough sun exposure.

Bone density assessment should be performed in all patients with short bowel syndrome and repeated every 2-3 years, annually in patients with osteoporosis. The identification of significant bone disease should lead to an assessment of calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D (25-hydroxy vitamin D), parathyroid hormone status, and the presence of metabolic acidosis. In patients receiving parenteral nutrition therapy, evaluation of parenteral nutrition formulations and additives is warranted. Conventional management includes exercise, exposure to sunlight, minimizing alcohol use, and eliminating tobacco. Replacement of calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D and correction of metabolic acidosis should be performed as needed. Because of the very poor bioavailability of bisphosphonates, intravenous agents are preferred in short bowel syndrome. It is advisable to consult an endocrinologist.

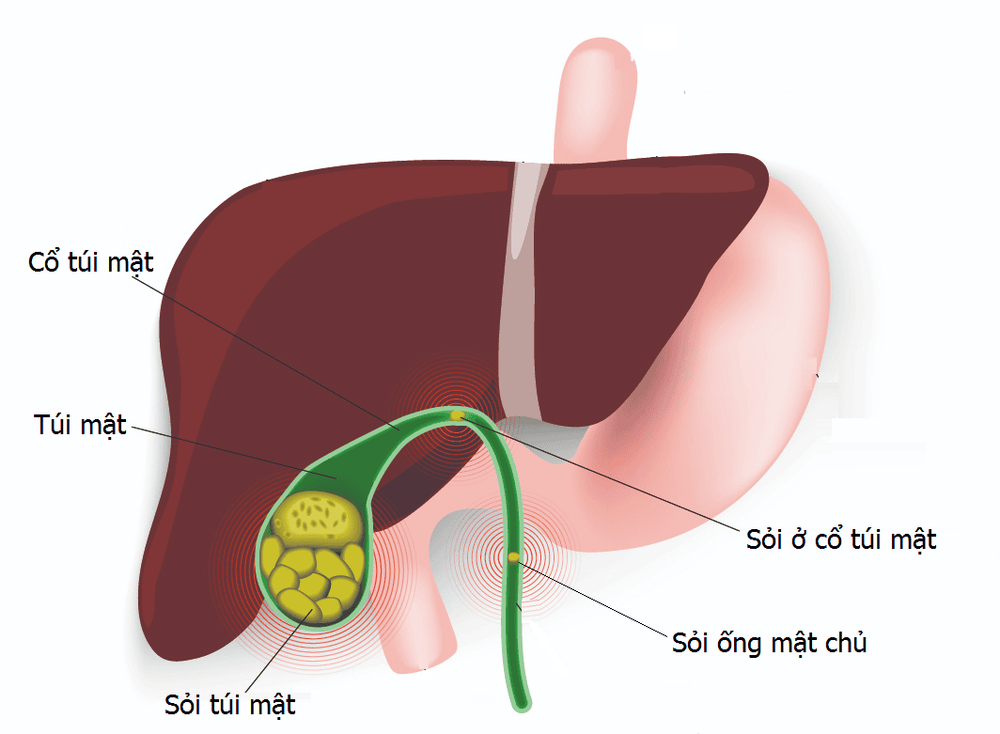

2.3 Liver dysfunction and gallstones Hepatobiliary complications including steatosis, cholestasis, and gallstones commonly occur in patients with short bowel syndrome and are due to the contribution of altered bowel anatomy and nutrition. outside the gastrointestinal tract need support. For this reason, 'intestinal failure-associated liver disease' is the preferred term to describe these complications. Fatty is commonly seen in adults while cholestasis is more common in children, both of which can progress to end-stage liver disease. The underlying mechanisms for the development of steatosis and cholestasis are different, although overlap occurs. The administration of >1 g/kg/day of parenteral lipids and the presence of chronic cholestasis are associated with the development of complex liver disease. Especially in those with rapidly deteriorating liver tests, sepsis should be considered when taking medications, supplements, other toxins, lack of bowel stimulation, altered bile acid metabolism, overgrowth SB levels, biliary obstruction and chronic liver disease including viral, autoimmune and metabolic disorders.

The composition of parenteral nutrition should also be considered as excess (energy content, dextrose, fat emulsion, methionine), deficiency (choline, essential fatty acids, carnitine, taurine, glutathione) and transmission time (continuous vs. cycle) can contribute. Lipid emulsion type (e.g. soybean-based [Intralipid, Fresenius Kabi or Liposyn, Abbott Laboratories], n-3 fish oil-based [Omegaven, Fresenius Kabi], combination of soy, medium-chain triglycerides, olive oil and oily fish [SMOF, Fresenius Kabi]) may also be important. In the United States, only soybean-based lipid emulsions are currently available unless approved under an investigational new prescription by the Food and Drug Administration. Correction of the identified cause or alteration of parenteral nutrition or lipid profile often leads to improvement in liver tests. The clinical use of ursodeoxycholic acid seems limited in this setting. In those who continue to progress, intestinal transplantation (with or without liver transplantation) should be considered. Correction of the identified cause or alteration of parenteral nutrition or lipid profile often results in improvement of liver tests. The clinical use of ursodeoxycholic acid seems limited in this setting. In those who continue to progress, intestinal transplantation (with or without liver transplantation) should be considered. Correction of the identified cause or alteration of parenteral nutrition or lipid profile often results in improvement of liver tests. The clinical use of ursodeoxycholic acid seems limited in this setting. In those who continue to progress, intestinal transplantation (with or without liver transplantation) should be considered.

Gallstones, usually cholesterol stones, occur in 40% of adults with short bowel syndrome, bile sludge formation being even more common. The main factor contributing to stone formation is decreased bile acid concentration due to altered enterohepatic circulation leading to gallstone formation. Gallbladder stasis, associated with decreased secretion of cholecystokinin in individuals with limited sugar intake, also contributes. Complications of gallstones appear to be more common in patients with short bowel syndrome than in the general population. Therefore, prophylactic cholecystectomy has been recommended in patients with short bowel syndrome when abdominal surgery is performed for other reasons.

3. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) seems to be common in patients with short bowel syndrome. The presence of intestinal dilatation and transitory alterations commonly seen in short bowel syndrome along with medications commonly used in these patients (eg, acid-suppressants and antispasmodics) supposedly facilitated the growth of SBBO. In a recent retrospective pediatric study, SBBO was strongly and independently associated with parenteral nutrition use but was not related to age, sex, baseline diagnosis, presence of valve ileus or use antacids. Although SBBO may have the potential benefit of enhancing energy extraction from poorly absorbed carbohydrates, excess bacteria in SB cause inflammatory and atrophic changes in the gut that impair absorption, acid binding Bile leads to indigestible fat. Consuming vitamin B12 leads to deficiency, causes some gas-related symptoms and aggravates diarrhea leading to decreased oral intake and potentially increases the risk of IFALD, an infection of intravenous catheters central and chronic gastrointestinal bleeding.

Some limitations of the tests used to diagnose SBBO exist (eg, most commonly SB aspiration with quantitative bacterial cultures and hydrogen breath testing), which makes it unsurprising. Diagnosis of SBBO in short bowel syndrome becomes difficult. This is especially so with the breath test, which, due to its rapid intestinal transit, makes it difficult to distinguish between SB and hydrogen production in the colon. Therefore, empiric antibiotic therapy is often offered. This may be reasonable in the context of a short bowel syndrome with a high likelihood of SBBO, however, treatment goals need to be clearly defined given the nonspecific nature of the existing symptoms and adverse effects. Potential side effects costs associated with antibiotic use. A variety of oral broad-spectrum antibiotics can be used with success based on improvement in symptoms. Continuous use of low-dose antibiotics in short bowel syndrome may be necessary to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance, so periodic rotation of the antibiotic used or the use of a poorly absorbed antibiotic is recommended. Although evidence from controlled studies to support their use is lacking, other strategies to control SBBO include limiting the use of antisecretory and antispasmodic agents, limiting carbohydrates, Intermittent colonic lavage with polyethylene glycol, use of probiotic agents and bowel slimming action.

Short bowel syndrome occurs in about 15% of adults who have a bowel resection, nearly 75% as a result of a single major surgery, and the remaining 25% as a result of multiple surgeries. About 70% of people with newly acquired short bowel syndrome are eventually discharged. Reports from the US and France have demonstrated the 2-year and 5-year survival rates of short bowel syndrome to be more than 80% and 70%, respectively. Survival was lowest in the terminal jejunostomy group and the ultra-short small bowel group (<30cm without colon). Parenteral nutrition dependence in the last 1, 2 and 5 years was reported as 74%, 64% and 48 %, respectively.3 In the multivariate analysis, parenteral nutrition dependence was reported decrease with residual colon >57% and rest length of SB >75 cm. In this study, more than 25% of patients who ended up completely weaned from parenteral nutrition did so >2 years after their last bowel resection. Other factors affecting survival in short bowel syndrome include the patient's age, primary disease course, comorbidities, the presence of chronic intestinal obstruction, and the experience of the management team. Human.2

Short bowel syndrome is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, reduced quality of life, and high health care costs. Therefore, when there are signs of onset, patients should take the initiative to visit the hospital for in-depth advice from a specialist doctor.

Vinmec International General Hospital always ensures professional quality with a team of doctors, modern equipment and technology. The hospital provides comprehensive, professional medical examination, consultation and treatment services, with a civilized, polite, safe and sterile medical examination and treatment space. Therefore, when there are health problems, customers can go to the hospital for advice and appropriate instructions from a team of experienced doctors.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.

References

John K. DiBaise, Carol Rees Parrish, Short Bowel Syndrome in Adults – Part 1 Physiological Alterations and Clinical Consequences, Nutrition issues in gastroenterology, series

132, Practical gastroenterology • august 2014. 1. O'Keefe SJ , Buchman AL, Fishbein TM, Jeejeebhoy KN, Jeppesen PB, Shaffer J. Short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure: consensus definitions and overview. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jan;4:6-10. Dabney A, Thompson J, DiBaise J, et al. Short bowel syndrome after trauma. Am J Surg 2004;188:792-795. 3. Amiot A, Messing B, Corcos O, Panis Y, Joly F. Determinants of home parenteral nutrition dependency and survival of 268 patients with non-malignant short bowel syndrome. Clin Nutr 2013;32:368-374. Thompson JS, DiBaise JK, Iyer KR, et al. Postoperative short bowel syndrome. J Am Coll Surg 2005;201:85-89