This is an automatically translated article.

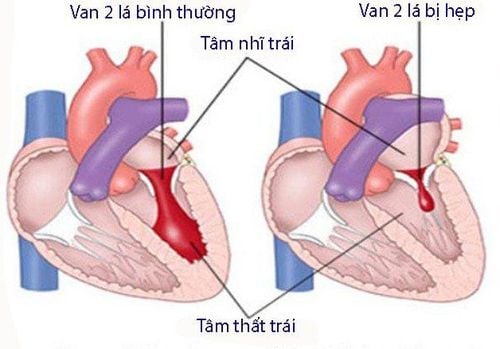

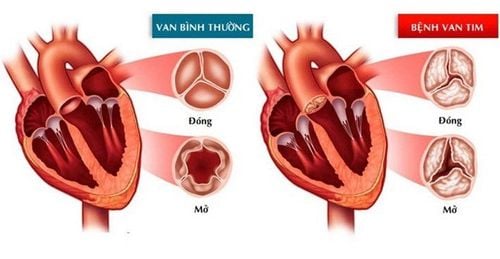

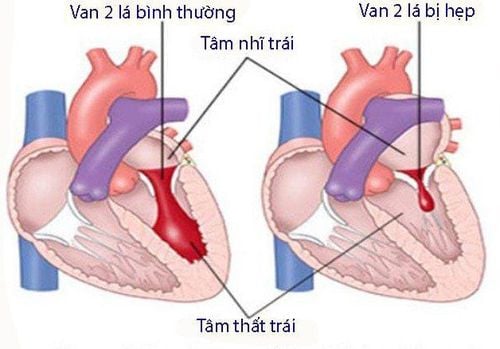

The article was written by MSc Ho Thi Xuan Nga - Anesthesiologist - Cardiovascular Center - Vinmec Central Park International General HospitalHeart valves help direct blood flow into and out of the heart. Any problem with the heart valves is extremely dangerous for health. The following are the basic principles of valvular anesthesia.

1. Basic principles of anesthesia for valvular disease

1.1 Loading fee

Total blood volume is increased to maintain effective systemic flow, due to volume loss posterior to the ventricular and atrioventricular (T) narrowing site. Blood volume decreases due to more systemic flow than to the regurgitated portion, because atrioventricular valve leaks "steal" volume in the low-pressure system of the left atrium. Tolerance to hypovolaemia is low, and so during anesthesia, preload should be kept between normal to high.1.2 Afterload

The ventricle (T) acts as a chamber with two retrograde volume escape routes directly related to contractile function, the systemic vascular resistance must therefore be completely low. It is necessary to use anesthetic agents with vasodilator properties (isoflurane, nitroprusside, phentolamine).1.3 Contraction function

It should be kept high to ensure presystolic flow. Therefore, only inotropes with no alpha effect (dobutamine, isoprenaline, amrinone, milrinone) should be used. In difficult cases, aortic balloon counterpulsation is very effective in providing ventricular (T) support, reducing mitral regurgitation, and improving coronary perfusion.1.4 Heart rate

It is important to maintain a high level because bradycardia increases filling time and ventricular volume, thereby increasing the risk of acute ventricular dilatation (T). Since mitral regurgitation occurs during systole, the frequency variation does not change its duration much. Maintaining sinus rhythm is important as long as the atria (T) are not very dilated.1.5 Pulmonary Arterial Resistance

Pulmonary hypertension is frequent but generally moderate; Pulmonary vascular system is hyper-reactive; Avoid any pulmonary vasoconstriction (hypoxia, hypercarbia, acidosis, N 2 O) and maintain ventilation for a pH of 7.5 and a PaCO of 32-35 mmhg.1.6 Positive pressure ventilation

Helps improve left-sided flow because right-cardiac venous return is still well maintained, pre-mitral flow is increased, and trans-atrial pressure is reduced; reduce ventricular (T) load effectively.2. Basic principles of anesthesia for valvular stenosis

2.1 Preload

It is necessary to keep the level high to ensure sufficient pressure gradient across the mitral valve, but the pulmonary vascular bed is not elastic because of chronic overload. In cases of hypovolemia or increased venous return (Trendelenburg position), there is an increased risk of acute pulmonary edema. Hypovolemia is very poorly tolerated because reduced mitral outflow is related to a decrease in atrial pressure (T) and cannot be compensated for by tachycardia.2.2 Afterload

Systemic vascular resistance should be kept high to compensate for the reduced systolic volume; The contractile function of the ventricles (T), which is usually preserved, supports the subsequent increase in load. Avoid any dilation of blood vessels. An alpha vasoconstrictor is the best way to maintain systemic pressure during surgery.2.3 Contraction ability

Ventricular (T) function is preserved; systolic volume is low and fixed. Beta-catecholamines are used only in relation to an excessive decrease in cardiac output (decrease in SvO2), as they are not beneficial for the ventricles (T) for two reasons: 1) tachycardia reduces ventricular filling (T) ) and 2) increased cardiac output increasing the pressure gradient across the mitral and atrial (T) valves.2.4 Heart rate

It is essential to remain low to allow very slow ventricular filling.2.5 Pulmonary artery pressure

Pre-capillary (arterial vasoconstriction) and post-capillary (venous hypertension) pulmonary hypertension. The risk of arterial vasoconstriction is increased in the presence of hypoxia, hypercapnia, acidosis or N20; Ventilation should be increased (PetCO2 30 mmHg), avoiding high ventilation pressure so as not to increase ventricular afterload (P). Pulmonary vasodilators are indicated if ventricular failure (P).2.6 Positive pressure ventilation

It is very beneficial for left-sided flow because venous return to the right heart is still well ensured and ventricular (P) is not impaired. Positive-pressure ventilation increases atrial return (T), reduces atrial infusion pressure, and improves valvular blood flow and reduces blood stasis.Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.

REFERENCES:BONOW RO, BRAUNWALD E. Valvular heart disease. Print: ZIPES DP, et al, eds. Braunwald's heart disease. A textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 7th edition. Philadelphie: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, 1553-632 BORROW K, GREEN LH, MANN T, et al. End-systolic volume as a predictor of postoperative left ventricular performance in volume overload from valvular regurgitation. Am J Med 1980; 68:655-60 BOUDOULAS H, KOLIBASH, AJ, BAKER P, et al. Mitral valve prolapse and the mitral valve prolapse syndrome: A diagnostic classification and pathogenesis of symptoms. Am Heart J 1989; 118:796-803 BRAUNBERGER E, DELOCHE A, BERREBI A, et al. Very long-term results (more than 20 years) of valve repair with Carpentier‘s techniques in non-rheumatic mitral valve insufficiency. Circulation 2001; 104(suppl I):8-11 BRAUNWALD E, ANTMAN E, BEASLEY JW, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 2000; 102:1193-209 BRUCE CJ, CONNOLLY HM. Right-sided valve disease deserves a little more respect. Circulation 2009; 119:2726-34 CARABELLO THREE. Aortic stenosis. Cardiol Rev 1993; 1:59-68 CARABELLO BA. Clinical practice: aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:677-82 CARABELLO BA. Aortic regurgitation: a lesion with similarities to both aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation. Circulation 1990: 82:1051-3 CLICK RL, ABEL MD, SCHAFF HV. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography: 5-year prospective review of impact on surgical management. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:241-7 COHEN DJ, KUNTZ RE, GORDON SPF, et al. Predictors of long-term outcome after percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:1329-35 ENDER J, EIBEL S, MUKHERJEE C, et al. Prediction of the annuloplasty ring size in patients undergoing mitral valve repair using real-time three-dimensional transoesophageal echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr 2011; 12:445-53 FLEISHER LA, BECKMAN JA, BROWN KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for non-cardiac surgery: Executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:1707-32 GREEN SJ, PIZZARELLO RA, PADMANABHAN VT, et al. Relation of angina pectoris to coronary artery disease in aortic valve stenosis. Am J Cardiol 1985; 55:1063-8 GRIGIONI F, TRIBOUILLOY C, AVIERINOS JF, et al. Outcomes in mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets: a multicenter European study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2008; 1:133-41 GROSSMAN W, ed. Cardiac catheterization and angiography. 3rd edition. Philadelphia, Lea and Febiger, 1986, 378 IUNG B, CACHIER A, BARON G, et al. Decision-making in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis: why are so many denied surgery ? Eur Heart J 2005; 26:2714-20 KAPLAN Joel.A, Cardiac Anesthesia for cardiac and non-cardiac surgery, 7th edition. Elservier, 2017, 1453-236 KERTAI MD, BOUTIOUKOS M, BOERSMA M, et. Aortic stenosis: An underestimated risk factor for perioperative complications in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Med 2004; 116:8-13 KLEIN AL, BURSTOW DJ, TAJIK AJ, et al. Age-related prevalence of valvular regurgitation in normal subjects. A comprehensive color flow examination of 118 volunteers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1990; 3:54-63 KWAK J, ANDRAWES M, GARVIN S, et al. 3D transesophageal echocardiography: a review of recent literature 2007-2009. Curr Opin Anesthesiol 2010; 23:80-8 MARWICK TH, STEWART WJ, COSGROVE DM. Mechanisms of failure of mitral valve repair: An echocardiographic study. Am Heart J 1991; 122:149-56 McCRINDLE BW. Independent predictors of immediate results of percutaneous balloon aortic valvotomy in children. Am J Cardiol 1996; 77:286-93 MILLER FA. Aortic stenosis: Most cases no longer require invasive hemodynamic study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989; 13:551-8 MILLER F, CALLAHAN J, TAYLOR C, et al. Normal aortic valve prosthesis hemodynamics: 609 prospective Doppler examination. Circulation 1989; 82:Suppl 2:II-169