This is an automatically translated article.

Posted by Master, Doctor Mai Vien Phuong - Department of Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Central Park International General Hospital

Achieving an adequate fluid and electrolyte supply can be difficult for patients with ileostomy. It is even more difficult for people with short bowel syndrome (SBS). .

1. Introduction

Dehydration is often easy to identify in patients with a large amount of stool, as the clinician can estimate stool output by the number of times the patient discards their colostomy device over a 24-hour period (Important in clinical practice: it is important to ask the patient, "In a 24-hour period" or "during the day, and then, what about at night?") . In contrast, the recognition of dehydration in a patient without a colostomy can be difficult, as the clinician cannot rely on the number of bowel movements per day to accurately quantify the volume of fluid lost. .

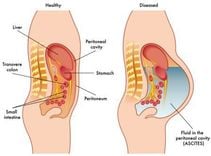

Approximately 4 liters of fluid (0.5L of saliva, 2L of gastric acid and 1.5L of pancreatic secretions) are normally secreted into the intestinal lumen each day in response to food and drink. In patients with <100 cm of jejunum, the daily volume of jejunostomy may be more than 4 liters per day.

Electrolyte disturbance is a major cause of pathology in patients with short bowel syndrome. In particular, people with a terminal jejunal resection lose large amounts of sodium in their stools, often leading to chronic sodium loss and dehydration. Clinicians not only teach short bowel syndrome patients what to expect in terms of colostomy/output, but also the underlying symptoms and risk of dehydration.

Fluid and electrolyte disturbances predominate in the early clinical course after macroscopic resection. These problems can persist for a long time, especially in patients without a colon where significant loss of bowel volume can lead to severe dehydration, kidney stones, kidney failure, ongoing metabolic acidosis, hypokalemia, hypokalemia, and hypocalcemia.

2. Assessment of dehydration

Initial evaluation of all patients with short bowel syndrome should include history of weight change, medication use, signs/symptoms of electrolyte deficiency, gastrointestinal or other possible symptoms. affect drinking or dehydration (nausea, vomiting, bloating, abdominal distension, etc.). The physical examination should also evaluate for malnutrition and for signs of dehydration and nutrient deficiencies. Serial weight measurements are useful for monitoring trends and serving as a warning of nutritional damage.

Patients with short bowel syndrome are required to be instructed to measure and record their daily fluid intake and urine/faecal output to help guide fluid needs. Sufficient water was considered present when urine output > 1L/day and urinary sodium concentration > 20 mEq/L.

Conventional laboratory parameters for assessing dehydration such as serum sodium, creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen are unreliable in short bowel syndrome because they become abnormal only after severe dehydration. This is because normal homeostatic mechanisms including plasma renin elevation and secondary aldosteronism occur in response to a slight decrease in serum sodium or blood volume. Sodium, and therefore water, is carefully conserved by the kidneys, so an increase in the ratio of BUN to creatinine is a late response and occurs only after the patient is significantly dehydrated.

3. Treatment of dehydration

Patients (and some physicians) often believe that large amounts of water should be consumed to compensate for the loss of stool during treatment for short bowel syndrome. However, this misconception often leads to increased colostomy volume and creates a vicious cycle that exacerbates fluid and electrolyte disturbances. Patients are often surprised to find that the amount of stool/excretion is significantly reduced after a twenty-four hour test, when they are given only appropriate solids and no oral fluids (intravenous fluids may be required). during the test to prevent dehydration).

In short bowel syndrome patients with excessive thirst due to dehydration, oral fluids should be limited to <1500mL/day and additional intravenous fluids should be given to maintain blood volume. Short bowel syndrome patients may benefit from replacing usual beverages/liquids with an oral rehydration-electrolyte solution (ORS) to enhance intestinal absorption and reduce fecal excretion.

The ability to maintain tidal volume while ingesting ordinary liquids by mouth is often dependent on the presence or absence of a colon. Most patients with short bowel syndrome have a colon that can be tolerated by oral hypoglycemic fluids. They are usually able to maintain adequate hydration and sodium balance without excessive dehydration. Patients without a colon typically require sodium supplementation (~90mEq or ~2 g sodium (7/8 teaspoon of table salt) for every liter of stool lost — in enteral patients, the sodium content in formula should be up to ~90 -100mEq/liter7 (1/4 teaspoon table salt = 600mg/26mEq sodium) if no other source of sodium is available.

4. Special considerations

Hypomagnesemia

Like chronic sodium depletion, hypomagnesemia can also be a problem in short bowel syndrome. It occurs as a result of many factors including magnesium malabsorption aggravated by binding to magnesium by unabsorbed fatty acids and increased renal excretion due to sodium/water depletion (and subsequent is hyperaldosteronism). The main clinical manifestations include convulsions, tremors, asthenia, lethargy, convulsions, coma, and electrocardiographic abnormalities. Hypomagnesemia may contribute to hypocalcemia due to impaired parathyroid hormone (PTH) release.

Oral magnesium salts can be used at doses of 12-24 mEq/day and is unlikely to increase colostomy, especially when administered at night when bowel transit is slowest. However, higher doses are often needed and can be difficult to use because the laxative effect of oral magnesium causes more severe diarrhea.

Magnesium heptogluconate is available as a liquid that can be added to ORS (see below) at a dose of 30 mEq/L. Oral administration of 1a-hydroxycholecalciferol may also be helpful as it can increase intestinal absorption of magnesium and kidney. If moderate to severe hypomagnesemia (<1 mg/dL) persists, parenteral magnesium sulfate may be required. Intravenous magnesium replacement should be administered over 8-12 hours (instead of the usual 1-4 hour intravenous administration) to prevent significant renal excretion when the renal threshold is exceeded.

Metabolic acidosis

Bicarbonate

Metabolic acidosis can arise from excessive loss of bicarbonate through the gastrointestinal tract. Acidosis may be further aggravated by impaired renal homeostasis due to salt and water depletion. In relation to patients with short bowel syndrome, chronic acidosis can lead to bone resorption and bone loss, exacerbation of secondary hyperparathyroidism, increased protein catabolism, decreased respiratory reserve, and malaise.

Metabolic acidosis can be detected on laboratory testing by finding low serum bicarbonate (or CO2). Patients with short bowel syndrome may have a normal anion gap or a hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis.

In patients with metabolic acidosis, alkaline therapy (usually with oral sodium bicarbonate) is used to maintain normal serum bicarbonate levels. Bicarbonate solutions such as bicitra may prove to be more beneficial than sodium bicarbonate tablets because of the number of tablets required for the equivalent amount of bicarbonate in bicitra. Occasionally, parenteral alkylation therapy may be necessary.

D-lactic acidosis

D-lactic acidosis is a rare neurological syndrome associated with short bowel syndrome that is characterized by altered mental status ranging from confusion to coma, slurred speech, convulsions jerking and loss of air conditioning. D-lactic acidosis resulting from bacterial fermentation of unabsorbed carbohydrates is seen in patients with short bowel syndrome, especially children, with a residual colon.

The development of this syndrome requires carbohydrate malabsorption with enhanced nutrient delivery to the colon, ingestion of large amounts of carbohydrates (usually concentrated sweets), D-lactate-producing bacteria, and D-lactate-producing bacteria. impaired D-lactate metabolism. While the optimal treatment for this condition is unclear, options include a carbohydrate (sugar)-restricted diet and the use of antibiotics to reduce the production of D-lactate-producing gut bacteria.

5. Flexible options for people with short bowel syndrome

Patients with short bowel syndrome may lose large amounts of fluids and electrolytes due to diarrhea/excessive secretions and sometimes due to the presence of disintegrating gastrointestinal/intestinal tubes. Fluids should be provided to compensate for all losses and maintain a urine output of at least 1L/day. The sodium and glucose content of the fluid are important considerations, as inappropriate fluids exacerbate fluid loss in short bowel syndrome.

Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS)

The rationale for adding sodium to oral rehydration solutions is to replace lost sodium and promote water absorption. Water movement along the water gradient is approximately nine times greater in the proximal small intestine than in the distal small intestine.

Oral rehydration solutions are effective because they use a transport system in conjunction with glucose. Administration of ORS has been shown to enhance water and sodium absorption in patients with short bowel syndrome, and it has allowed some patients to discontinue IV fluid support. The optimal sodium concentration of ORS to promote jejunal absorption has been shown to be 90-120 mEq Na+/L 25 (with an optimal carbohydrate:sodium ratio of 1:1).

Although ORS therapy has been extremely successful in the treatment of diarrhea worldwide, it is not a panacea and in some patients with short bowel syndrome it can also increase the amount of diarrhea. feces. Furthermore, some patients may experience a loss of appetite. ORS should not be replaced with commercial sports drinks because sports drinks contain significantly higher carbohydrate content and lower sodium content than ORS. Potassium and magnesium may be added to ORS as gluconate salts (12mmol/L ORS) and heptogluconate (30 mmol/L ORS), respectively, if available. In fact, despite our best efforts, there are still some patients who refuse to take ORS.

Parenteral fluid

In some patients with short bowel syndrome after the acute phase, intravenous fluids without macronutrients may be needed for those who need fluids, but no calories. If the patient is unable to maintain urine output > 1 liter per day, additional intravenous fluids may be needed.

Intravenous fluid is usually given as one liter of normal saline infused over 2 to 4 hours once daily if needed. Although the composition of the solution may include only sodium chloride, dextrose, other electrolytes, vitamins, and bicarbonate may occasionally be added. As previously mentioned, ORS can be administered via a nasogastric tube as an infusion at night. During the hot summer months, patients receiving parenteral nutrition overnight may require additional intravenous fluids during the day to prevent dehydration and reduce potential kidney damage. Intravenous fluids may also be needed in patients with short bowel syndrome who have been successfully weaned from PN but occasionally require parenteral fluid support.

>> See also: Nutritional therapy for short bowel syndrome in adult patients - Posted by Doctor Mai Vien Phuong - Department of Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Central Park International Hospital

CONCLUSION

Maintaining hydration status is a central component in the care of patients with short bowel syndrome. Failure to do so can lead to dehydration, rapid weight loss, and fatigue. If chronic and untreated, it can also lead to kidney stones and jeopardize kidney function. Educating patients to recognize the signs of dehydration as well as instructing them on appropriate defenses against dehydration should be a top priority for clinicians caring for these patients.

Currently, Vinmec International General Hospital is a prestigious address trusted by many patients in performing diagnostic techniques for digestive diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, short bowel syndrome, diseases causing chronic diarrhea , Crohn's disease, ectopic gastric mucosa in the esophagus...

Vinmec Hospital with modern facilities and equipment and a team of experienced experts, always dedicated to medical examination and treatment, Customers can rest assured with gastroscopy and esophagoscopy service at Vinmec International General Hospital.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.

References

Carol Rees Parrish, John k. Dibaise, hydrating adult patient with short bowel syndrome, nutrition issues in gastroenterology, series

138, practicalgastro.