This is an automatically translated article.

Article by Doctor Vu Duy Dung - Department of General Internal Medicine - Vinmec Times City International General HospitalOnly about 30% of seizures are acquired, and the remaining 70% are likely caused by one or more genetic factors. Epilepsy genes follow a complex pattern, and most epileptic seizures will have a polygenic background with many sensor genes contributing to the disease. Next-generation sequencing technology has revolutionized gene discovery in epilepsy and many other diseases.

1. Genetic causes of epilepsy

Genome-comparative hybridization is the first specific test for patients presenting with epilepsy and developmental delay, intellectual disability, and/or dysmorphic features. In patients with generalized epilepsy and genetic intellectual disability, genomic hybridization was able to detect a copy number variant in 28% of cases. Copy number variations have been identified in approximately 1% of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Genotypic and phenotypic variation is found in most genetic epilepsy, and single-gene testing has been widely replaced by gene panels and whole-exon sequencing. Gene panels are either targeted for a specific phenotype, for example, a progressive myoclonic epilepsy, or provide a complete epilepsy gene panel. Whole-exon sequencing and whole-genome sequencing are typically performed in a genomic clinic setting and a research program with access to genomic counseling and the ability to analyze and interpret genetic information. unknown variant.

Dravet syndrome is the best known epileptic encephalopathy with an isolated clinical presentation accompanied by a pathological variant in the SCN1A gene in 80% of patients. Dravet syndrome usually presents with early-onset, prolonged febrile seizures, often caused by mild hyperthermia. Hypertonicity-convulsive, generalized, and hemitonic seizures are the most common. Myoclonic seizures appear late in the course of the disease. Patients often have cognitive impairment, ataxia, psychomotor regress, and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder-type behavior. However, the variable permeability of the gene and the severity of the phenotype make clinical manifestations challenging. Interestingly, 10% of generalized epilepsy families with febrile seizures plus (GEFS)+ are SCN1A positive, and family members are at greater risk of presenting with severe epilepsy. eg myoclonic-associated seizures or Dravet's syndrome. Many other genes have been reported to cause Dravet syndrome-like disorders, including SCN2A, SCN8A, SCN9A, SCN1B, PCDH19, GABRA1, GABRG2, STXBP1, HCN1, CHD2, and KCNA2, which require gene panel testing or analysis. whole exon sequence. Epileptic encephalopathies other than Dravet syndrome are associated with mutations in the genes CDKL5 , STXBP1 , SCN2A , SCN8A , KCNQ2 ; most are new mutations (de novo gene mutations). Recessive or mitochondrial or more complex inheritance is rare, including X-linked PCDH19 encephalopathy in the daughters of healthy male carriers.

Hội chứng Dravet cần được phát hiện sớm và điều trị kịp thời

Neurologists should be familiar with a small subset of genetic epilepsy that present with a somewhat distinct clinical phenotype and, if clinically indicated, may be tested with existing gene panels. available on the market. Notable gene-related epilepsy includes autosomal dominant partial seizures:

autosomal dominant temporal lobe epilepsy Nocturnal frontal lobe autosomal dominant epilepsy Familial with variable foci of epilepsy Autosomal dominant temporal lobe epilepsy is often associated with mutations in the LGI1 (30%) and RELN genes and has a permeability of 55% to 78%. Patients presenting with pronounced auditory prodromal or perceptual aphasia may progress to tonic-clonic seizures. Onset is usually in adolescence or early adulthood, and the typical patient will be intellectually normal and respond well to antiepileptic drugs. Autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy is often associated with mutations in the neuron's acetylcholine nicotinic receptor, which is found in 20% of patients with this condition. A more severe form with intellectual disability is associated with the KCNT1 mutation. Permeability is about 70% and seizures usually present in infancy to young adulthood, characterized by clusters of nocturnal seizures, which can be tonic, dystonia, or hyperactive, with 70% there is a nonspecific aura before the attack. The diagnosis is clinical, and the EEG is often vague or normal. The patients responded well to carbamazepine and zonisamide, but 30% were resistant. Familial partial seizures with variable focal epilepsy involve mutations in the DEPDC5, NPRL2, and NPRL3 genes, all components of the GATOR complex (Rag-directed protein activated by guanosine triphosphatase [GTPase] ]), which accounts for at least 10% of familial frontal lobe epilepsy. Patients present with variable epileptic foci and a permeability of 50% to 80%. Onset was 1 month to 51 years of age with a mean age of 12. Prolonged periods of remission during the adolescent/adult years have been reported.

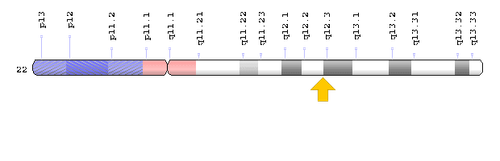

Hình ảnh mô tả phân đoạn một Gen điều hoà DEPDC5

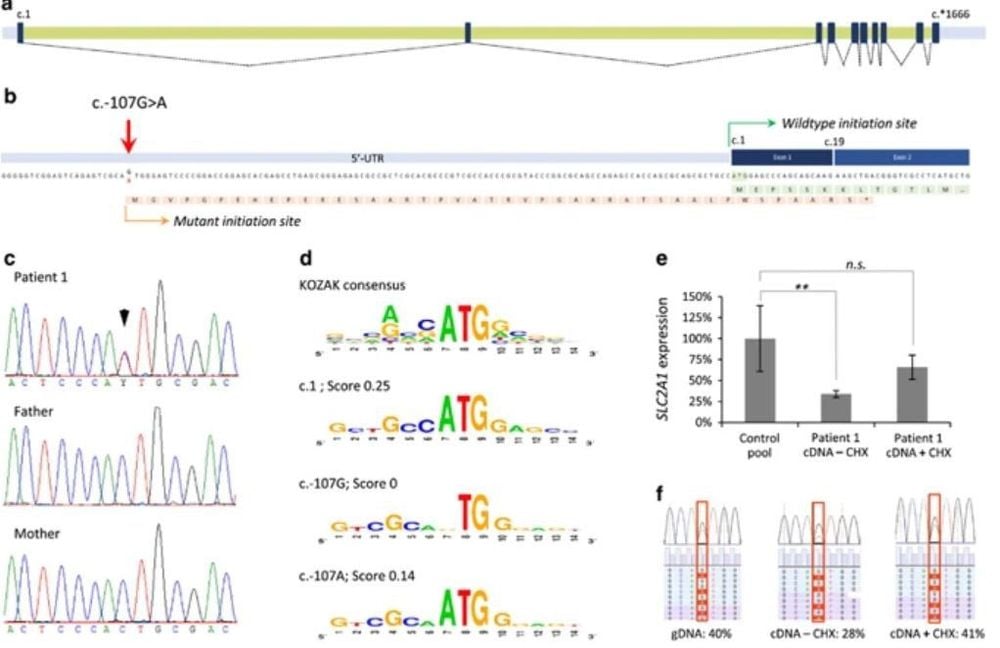

It is important to understand the glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) deficiency syndromes associated with the SLC2A1 gene mutation because of its excellent response to dietary modification and the recent discovery of variants late onset and milder. Typical manifestations are in the first months of life. Children often present with clustered seizures and status epilepticus during fasting (eg, before breakfast). Accompanying symptoms are usually severe psychomotor retardation, dystonia, ataxia, and acquired microcephaly. The syndrome may manifest as early-onset absence seizures and myoclonic-associated seizures. One diagnostic hint is low fasting CSF glucose. The disease has an excellent response to the ketogenic diet.

Periventricular nodular ectropion associated with a filamin A mutation is important to recognize because of its relevance to prenatal counseling in this X-linked dominant disease. It affects female patients who are usually intellectually normal and present with seizures in nearly 90% of cases. Forty-nine percent of classic bilateral periventricular nodular ectropions are associated with X-linked filament A mutations, which cause perinatal death in male carriers. As a result, half of the boys died, and half of the girls became ill.

Understanding the genetic cause of an individual with epilepsy has many clinical implications. A genetic diagnosis ends the diagnostic process and can avoid unnecessary testing or lead to important screening for known cancers or complications. There is a genetic aspect to some genetic epilepsy that affects prognosis and counseling for patients. Mitochondrial diseases presenting with epilepsy may not be recognized until adulthood and diagnosis has a direct impact on treatment and counseling for patients and their family members.

Detecting a specific gene abnormality could also open the door to precision medicine. A genetic abnormality may not only cause the disease but also be associated with a specific mechanism leading to seizures that may respond to specific treatment. SCN1A-associated Dravet syndrome responds well to drugs such as clobazam and valproate and may be aggravated by sodium channel blockers, whereas SCN8A-related Dravet syndrome may benefit from sodium channel blockers and Dravet syndrome related PCDH19 may respond well to steroids. The mammalian rapamycin target (mTOR) signaling pathways influence the regulation of reproduction and cell growth. Mutations in the mTOR pathway can lead to a wide spectrum of cortical developmental malformations from localized cortical dysplasia to hemispheric and cerebral hypertrophy, or can cause multi-organ diseases such as tuberous sclerosis or histiocytosis syndromes including Cowden and Lhermitte-Duclos disease. Several regulatory genes mTOR, DEPDC5, MTOR, NPRL3, PI3KCA, and PTEN, have been implicated in cerebral hemispheric hypertrophy and focal cortical dysplasia that cause injury and non-injury and may manifest as germ cell mutation or somatic cell mutation in the brain. In polyhydramnios, brain hypertrophy, and symptomatic epilepsy syndrome (PMSE), an autosomal recessive disorder commonly associated with mutations in the STRADA gene, treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin has been shown to prevent adverse events. seizures occur. In tuberous sclerosis, seizure control with everolimus, a synthetic synthetic mTOR inhibitor, is more variable in efficacy, suggesting that treatment before seizure onset may be decisive for prevention epilepsy.

Hội chứng thiếu chất vận chuyển glucose typ 1 (GLUT1) liên quan đến đột biến gen SLC2A1

Doctors who treat patients with epilepsy are often asked about genetic risk for epilepsy. In the absence of family history or evidence of a specific gene syndrome, the risk of epilepsy for the general population is estimated at 1%; for a child of a mother with epilepsy, 2.8% to 8.7%; for a child of a father with epilepsy, 1.0% to 3.6%. It is increased if the parental epilepsy begins before the age of 20. Genetic counseling for a specific epileptic syndrome may be straightforward in patients with a 100% permeation syndrome but will be complex in permeation situations. incomplete and new (de novo) mutations (eg, Dravet syndrome) and should be done with the help of a genetic counselor.

2. Comorbidities Epilepsy exhibits a bidirectional relationship with neurological (eg, stroke, migraine, dementia, traumatic brain injury) and psychiatric (eg, depression) emotions and anxiety) accompanies. Many diseases, including depression, anxiety, dementia, migraine, heart disease, stomach ulcers, and arthritis, are up to eight times more common in people with epilepsy than in the general population. Circulating comorbidities are seen even in seizure-free patients, and patients with inactivated epilepsy are still at increased risk of death at a young age, suggesting a systemic component implicated in the etiology of epilepsy. In order to fully understand the etiology of epilepsy, comorbidities and systemic vulnerabilities need to be noted and appropriately treated.

3. Conclusion

Evaluation of epileptic causes has changed notably over the past decade. There is greater importance in distinguishing acute symptomatic seizures with triggers (requiring treatment of the underlying medical condition) from an unprovoked seizure, which may already be epilepsy. . There is a growing acceptance and elucidation of the term epilepsy as the most common cause of recurrent seizures. The new classification of epilepsy does not stop at recognizing specific epilepsy syndromes but also aims to recognize the underlying cause. This could lead to an early identification of candidates for surgery, a better understanding of many epileptic encephalopathies, and, over time, promising medical treatments that target the underlying underlying causes. sick.

Source:

Stephan US. Evaluation of Seizure Etiology From Routine Testing to Genetic Evaluation. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2019;25(2, Epilepsy):322–342

Please follow the series of articles on "Evaluating seizure causes from routine tests to genetic testing" by Dr. Vu Duy Dung including:

Part 1: Assessing seizure causes from routine tests Refers to genetic testing Part 2: New-onset seizures Part 3: Epileptic assessment Part 4: Extra-genetic causes of epilepsy Part 5: Genetic causes of epilepsy