This is an automatically translated article.

The article was professionally consulted with Senior Doctor, Specialist II Doan Du Dat - General Internal Medicine - Department of Medical Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Ha Long International Hospital.The body's inflammatory response can be acute (lasting for several days) aka acute inflammation, or it can be chronic (response to persistent and unresolved insult). The inflammation can develop into permanent tissue damage or fibrosis. In this article, we will review the processes involved in the mechanism of acute inflammatory response.

What is an inflammatory response: Inflammation is the body's normal protective response to damage caused by pathogens. Inflammation occurs when white blood cells in the body increase their activity to protect the body from being attacked by pathogens.

The key clinical features of acute inflammation (swelling - heat - redness - pain) have been recognized for at least 5000 years. Dr. John Hunter, famous late 18th century Scottish surgeon, observed that the inflammatory response was not a disease but a nonspecific and initiating response of activity. of the immune system. Through his microscopic examination of important transparent membrane preparations, German pathologist Julius Cohnheim concluded that the inflammatory response is essentially a vascular phenomenon. The phenomenon of phagocytosis was described in the late 19th century by Elie Metchnikoff and his colleagues at the Pasteur Institute. Morphological studies, using both live animals and fixed histological preparations, have changed our understanding of inflammation and led to the currently held concepts of hemodynamic changes associated with inflammation, acute inflammation and chronic inflammation. During the last 5 decades, modern techniques in biochemistry, tissue culture, monoclonal antibody production, recombinant DNA technology, and genetic manipulation of isolated cells and whole animals have enabled a more detailed understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the inflammatory response, the active resolution of inflammation, and the transition to tissue repair and restoration.

1. What is an acute inflammatory reaction?

Inflammation is the initial physiological response to tissue damage, such as a mechanical, thermal, electrical, irradiation, chemical, or infection response. The acute inflammatory response is consistently marked by microvascular leakage and neutrophil accumulation. The four basic markers of acute inflammation, mentioned above, can be counted in the physiological parameters of inflammation. The systemic effects of inflammation, especially acute inflammation, are responsible for the familiar clinical signs of fever, acute phase reaction, and altered sensation. Sepsis, in turn, is a systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome that occurs in response to infection; severe sepsis is sepsis complicated by acute organ dysfunction; and septic shock is sepsis complicated by hypotension, resistance to fluid resuscitation, or hyperlactatemia.Acute inflammatory state, including local changes in blood flow, changes in microvascular permeability and neutrophil secretion. In addition to hemodynamic changes, inflammation includes endothelial cell activation, low-affinity leukocyte-endothelial adhesions, high-affinity or stationary leukocyte-endothelial adhesion interactions, and leukocyte migration. platelets, leukocyte activation, and subsequent reduction and resolution of the inflammatory response. The highly regulated migration of leukocytes from the vasculature into sites of inflammation and lymphocytes through secondary lymphoid tissues and in turn, into sites of microbial invasion, is essential for host defense. host in the context of inflammation and immunity. This extraordinary complexity of regulatory processes that control inflammation is exemplified by, but not limited to, proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, interleukin [...] IL]-1β, IL-6) leads to inflammation, counteracting the increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-4, IL-10, IL-11, IL-13, variable growth factor [TGF-β]-β, IL-1ra and soluble cytokine receptors) reduce the inflammatory response. Both termination of the inflammatory process and the transition from an active inflammatory environment to a tissue remodeling, wound healing environment are positively regulated processes. These mediators range from short-lived reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates to the entire regulatory system (eg, complement and coagulation). Many inflammatory mediators have become targets for intermittent therapeutic strategies.

2. Mechanism of acute inflammatory response

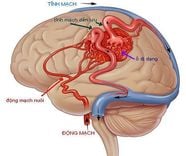

2.1. Hemodynamic Changes that occur early in acute inflammation include arteriolar vasodilation and local increase in microvascular permeability. In many cases, arteriolar vasodilation is followed by a period of rapid and transient vasoconstriction. Arterial vasodilation leads to increased blood flow, thus explaining the familiar swelling, heat, and redness that characterize the site of acute inflammation. An increase in blood flow, together with an increase in microvascular permeability, leads to hemoconcentration and local increase in viscosity. These hemodynamic changes are important for subsequent leukocyte migration because selectin-mediated rolling endothelial-leukocyte adhesion interactions occur only under such low shear conditions. Increased microvascular permeability leads initially to a protein-poor shift, followed by a protein-rich plasma secretion, another feature of acute inflammation.

Sự thay đổi huyết động tác động lên cơ chế của phản ứng viêm cấp

Changes in local blood flow occur at the level of arterioles, the key to vascular resistance and are largely regulated by the autonomic nervous system, nitric oxide (NO) (formerly known as endothelium-derived relaxation factors), vasoactive peptides, and eicosanoids. Many soluble chemical mediators can increase microvascular permeability through some of the above-mentioned mechanisms.

2.2. Leukocytes Selection (mobilization) of leukocytes to the site of inflammation is a fundamental feature of the inflammatory response. Organized recruitment of specific types of leukocytes to specific tissues, whether to sites of acute inflammation, during physiological lymphocyte recirculation through lymph nodes, or during an immune response of the cell to microbial colonization, is called homing.

The general mechanisms of leukocyte migration are similar, but leukocytes and specific mediators differ. For example, neutrophils bind to and traverse postcapillary venules during acute inflammation, T lymphocytes never bind to and traverse the superior endothelial venules of the lymph nodes. Lymphocyte (HEV) in circulating lymphocytes, and effector and memory T lymphocytes bind to and traverse postcapillary endothelial cells at sites of chronic infection.

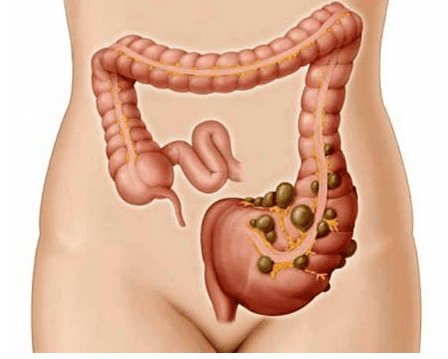

The importance of leukocytes in host defense is emphasized in patients with leukocyte counts or functional defects. White blood cells are important because of their central role in phagocytosis and the killing or suppression of bacteria and the digestion of necrotic tissue debris. Leukocyte-derived products, such as proteolytic enzymes and reactive oxygen species, contribute to tissue damage.

2.2.1. Leukocyte adhesion and migration Vascular stasis results from the hemodynamic changes of early acute inflammation leading to migration of leukocytes from the central column of circulating blood cells to locations along the endothelial surface.

This process, or this combination (margination), is enhanced in conditions of slow bleeding. Leukocytes adhere firmly and weakly to the endothelial surface. Live membrane preparations and flow chamber studies using endothelial cell monolayers and suspensions of purified leukocytes have shown that cells "tumble and roll" along the endothelial surface tissue. Mild, weak, transient neutrophil endothelial adhesion interactions occur within minutes of the onset of the acute inflammatory response and may, depending on the time in the progression of the inflammatory response, involving neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, basophils, or eosinophils. The endothelial cell–leukemic cell–cell adhesion interaction is a specific and necessary step prior to high-affinity, or static adhesion and migration. Early rolling adhesion interactions were accomplished primarily by selectins and their carbohydrate-rich reactants. In turn, cell surface expression of selectins (and other intercellular adhesion molecules) is regulated by locally produced proinflammatory mediators.

Cơ chế của phản ứng viêm cấp ảnh hưởng bởi sự ứ trệ mạch máu

Khi các tế bào nội mô tiếp xúc với histamine, thrombin, yếu tố hoạt hóa tiểu cầu (PAF) hoặc yếu tố mô, P-selectin đã được tạo sẵn sẽ nhanh chóng (trong vòng vài phút) được chuyển vị trí nhanh chóng (trong vòng vài phút) đến bề mặt nội mô, nơi nó tham gia vào các bạch cầu đã kết hôn thông qua các phân tử carbohydrate có chứa dư lượng axit sialic (ví dụ, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 [PSGL-1]). Tương tác liên kết thoáng qua, có ái lực thấp này giải thích một phần cho các tương tác cuộn sớm. Sự phát triển của chuột loại trực tiếp (tức là thiếu selectin riêng lẻ [P - / -; E - / - hoặc L - / -], chuột loại trực tiếp đôi (ví dụ: E - / - và P - / -), và thậm chí là loại trực tiếp ba lần chuột, đã xác nhận rằng bạch cầu lăn có thể được gần như hoàn toàn chiếm bởi selectin. phơi sáng của các tế bào nội mô để TNF- α hoặc IL-1 β kết quả trong protein biểu hiện tổng hợp phụ thuộc mới của E-selectin, một phản ứng xảy ra trong vòng 1 đến 2 giờ và cao nhất là 4 đến 6 giờ.

Như trong trường hợp kết dính bạch cầu qua trung gian P-selectin, sự kết dính qua trung gian E-selectin xảy ra thông qua một loạt các gốc carbohydrate được sialyl hóa và fucosyl hóa liên quan đến các kháng nguyên nhóm máu sialyl Lewis X và sialyl Lewis A, nhưng được tìm thấy trên bạch cầu. Chất đối kháng Selectin bao gồm một số glycoprotein giống mucin khác nhau được bao phủ bởi các phần tử sialyl khác nhau. L-selectin được biểu hiện thành phần bởi bạch cầu, tham gia vào liên kết bạch cầu trung tính và bạch cầu đơn nhân với nội mô hoạt hóa ở các vị trí viêm, di chuyển tế bào lympho-tế bào nội mô (ví dụ, tế bào lympho di chuyển đến các hạch bạch huyết thông qua HEV), tương tác kết dính bạch cầu-bạch cầu thông qua mucin- chứa lưu huỳnh giống như glycoprotein, và được phân cắt khỏi tế bào nhờ các enzym “giảm” như disgrin và metalloproteinase (ADAM) -17 (enzym chuyển đổi TNF-α [TACE]) khi bạch cầu được kích hoạt.

Các thụ thể đối kháng glycoprotein giống mucin có liên quan trên HEV được gọi chung là địa chỉ nút ngoại vi (PNAds) và bao gồm phân tử bám dính tế bào địa chỉ niêm mạc (MadCAM) -1, GlyCAM-1 và CD34. L-selectin rụng đi tạo điều kiện thuận lợi cho sự di chuyển của bạch cầu bằng cách cho phép tế bào bạch cầu kết dính yếu tách ra khỏi nội mạc. Tương tác kết dính lăn có ái lực thấp tạo tiền đề cho các tương tác kết dính có ái lực cao qua trung gian β -và globulin miễn dịch và sự di chuyển bạch cầu.

Các tương tác cán mỏng qua trung gian selectin và chất kết dính tĩnh có ái lực cao không hoàn toàn rời rạc về mặt thời gian hoặc cơ học. Ví dụ, TNF- α và IL-1 β đều cảm ứng E-selectin, không được biểu hiện bởi các tế bào tĩnh lặng, và cả hai đều làm tăng biểu hiện nội mô của phân tử kết dính gian bào (ICAM) -1 và phân tử kết dính tế bào mạch (VCAM) -1, được thể hiện một cách cấu thành ở mật độ bề mặt tế bào thấp. ICAM-1 tham gia vào việc tuyển dụng tất cả các loại bạch cầu và VCAM-1 tham gia vào việc tuyển dụng các bạch cầu viêm mãn tính (tế bào lympho, bạch cầu đơn nhân, bạch cầu ái toan và basophils). ICAM-1 liên kết với Tích phân β 2 (bạch cầu), là cấu trúc dị số có chứa một loại chuỗi α (ví dụ: CD11a, CD11b, CD11c, CD11d) và chuỗi β chung (CD18). VCAM-1 liên kết với tích phân β 1 (ví dụ, kháng nguyên rất muộn [VLA] -4 / α 4 β 1 ) Các tế bào nội mô được kích hoạt tiết ra PAF và CXCL8 (IL-8), chúng hoạt hóa các bạch cầu liên kết với selectin bên trên.

Các dị phân tử CD11a / CD18 (LFA-1) của bạch cầu trải qua một sự thay đổi cấu trúc nhất thời và các nhóm phân tử CD11a / CD18 hình thành các cụm đa phân tử. Cả sự thay đổi cấu trúc trong CD11a / CD18 và sự phân nhóm đều góp phần làm tăng ái lực liên kết với ICAM-1 nội mô. CD11b / CD18 (Mac-1) liên kết với ICAM-1, ICAM-2 và iC3b (xem phần “Phần bổ sung”), phần sau của nó làm loại bỏ các hạt được phủ bổ thể. CD11c / CD18 cũng liên kết với iC3b và bắt đầu thực bào, nhưng đóng vai trò ít hơn trong việc kết dính bạch cầu trung tính so với CD11a / CD18 và CD11b / CD18. Các phân tử kết dính giữa các tế bào được tìm thấy trên nhiều loại tế bào khác nhau ngoài tế bào nội mô. Vai trò của CD11c / CD18, CD11d / CD18 và ICAM-3 trong kết dính bạch cầu-nội mô chưa được xác định rõ ràng. β 1 -Integrins, đặc biệt là VLA-4, được tìm thấy chủ yếu trên các bạch cầu viêm mãn tính (ví dụ, tế bào lympho, bạch cầu đơn nhân, basophils và bạch cầu ái toan) và làm trung gian gắn kết bạch cầu qua VCAM-1. β 1.Tương tác kết dính qua trung gian -integrin xảy ra thông qua chuỗi peptit axit arginine-glycine-aspartic (RGD) được hiển thị bởi VCAM-1, cũng như trên bề mặt tiếp xúc của các phân tử nền (ví dụ, fibronectin). Tương tác kết dính qua trung gian β 2 -Integrin – ICAM-1 và β 1 -integrin – VCAM-1 xảy ra muộn hơn (vài giờ đến vài ngày) trong phản ứng viêm so với tương tác qua trung gian selectin.

β 1 - và β 2 -integrins rõ ràng là rất quan trọng trong việc tuyển chọn bạch cầu vào các vị trí viêm cấp tính và mãn tính. Mười tám tiểu đơn vị tích phân α khác nhau , tám tiểu đơn vị tích phân β , và 24 tổ hợp heterodimer in vivo đã được xác định ở động vật có vú. Ngoài các tương tác kết dính tế bào nội mô-bạch cầu, các tích phân hoạt động trong một loạt các tương tác tế bào-tế bào và chất nền tế bào-ngoại bào khác. Một số lượng lớn các phân tử nhỏ, peptit và kháng thể thiết kế nhắm mục tiêu tích phân đã được phát triển cho các ứng dụng điều trị. Các bệnh về viêm - miễn dịch được điều trị bằng các chất đối kháng tích hợp bao gồm, trong số những bệnh khác, bệnh đa xơ cứng, bệnh Crohn và thoái hóa điểm vàng do tuổi tác.

Tương tác kết dính tĩnh tại có ái lực cao trước sự di chuyển của bạch cầu qua lớp nội mạc vào trung gian dưới da. Tầm quan trọng về mặt chức năng của tương tác kết dính giữa bạch cầu và nội mô đã được làm rõ bởi các nghiên cứu liên kết trong ống nghiệm và nghiên cứu in vivo đã sử dụng các kháng thể trung hòa chống lại các phân tử kết dính, chất đối kháng dược lý của các phân tử kết dính và chuột loại trực tiếp. Tầm quan trọng về mặt chức năng của tích phân bạch cầu (CD11a / CD18, CD11b / CD18, CD11c / CD18) cũng đã được nhấn mạnh bởi các quan sát lâm sàng và thực nghiệm ở những bệnh nhân mắc chứng thiếu kết dính bạch cầu di truyền hiếm gặp.

β 2 -Integrin ICAM-1 và ICAM-2, cũng như β 1 -integrin (VLA-4) VCAM-1, tạo ra các tương tác kết dính dẫn đến tổ chức lại tế bào trong bạch cầu làm phẳng và lan rộng trên bề mặt nội mô, mở rộng giả mô giữa các tế bào nội mô, và di chuyển dọc theo các gradient hóa học ngoại mạch. Hầu hết bạch cầu thoát ra khỏi không gian mạch máu giữa các tế bào nội mô liền kề (di cư nội bào). Sự di chuyển nội bào không chỉ phụ thuộc vào tương tác tích phân-phối tử mà còn phụ thuộc vào CD31 (PECAM-1 [phân tử kết dính tế bào nội mô tiểu cầu-1]) được biểu hiện trên cả bạch cầu và tế bào nội mô, và sự tháo rời thuận nghịch thoáng qua của nội mô mạch máu liên kết chặt chẽ (VE) - các phức chất liên kết cadherin. Có bằng chứng cho thấy bạch cầu cũng có thể thoát ra khỏi không gian mạch máu thông qua một con đường xuyên tế bào ít đặc trưng hơn.

2.2.2. Hóa chất và kích hoạt bạch cầu Các bạch cầu liên kết chặt chẽ với nội mô di chuyển từ khoảng không gian mạch vào kẽ bằng cách kéo dài các nang giả giữa các điểm nối gian bào (Các protease trung tính được tiết ra như elastase, cathepsin G và proteinase 3, đóng một vai trò trong việc di chuyển hoặc “xâm nhập” của bạch cầu qua chất nền ngoại bào dưới nội mô. Collagenase đặc biệt quan trọng trong việc di chuyển bạch cầu qua màng đáy.

Bạch cầu có sự liên quan với phản ứng viêm của cơ thể

Chemical factors for neutrophils include peptides of bacterial origin (eg, N-formyl peptide), peptides derived from complement (eg, C5a), lipid chemotaxis are derived from cell membranes (eg, PAF), and cytokines and chemokines are produced by a variety of cells (eg, CXCL8 [IL-8] from endothelial cells). Chemical factors vary according to their specificity for different types of leukocytes. For example, C5a and N-formyl peptide both induce neutrophil and monocyte chemotaxis, and CXCL8 [IL-8] induces neutrophil chemotaxis, while CCL2 (proteinization) monocyte therapy [MCP]-1) induces chemotaxis in monocytes and a specific subset of memory T lymphocytes. The Th17 subset of CD4 helper T lymphocytes secretes IL-17, and IL-22 participates in neutrophil recruitment. (There are several species of IL-17, including IL-17A–IL-17F homodimers as well as heterodimers.) Each of these chemotactic factors activates “target” cells by participating in Specific cell surface receptors are, therefore, associated with the cell's contractile motor.

In addition to chemoregulatory effects, cell surface and soluble mediators induce leukocyte activation as demonstrated by a variety of changes in cellular function (eg, regulation of leukocyte integration and increased binding affinity [eg, CD11b/CD18], selectin shedding [eg, L-selectin ], lysosome lysis and initiation of respiration). Major advances have been made in the understanding of the biochemical pathways involved in chemoregulation, cellular activation, and degradation. Although there are nuances in the signaling pathways involved in these processes, several themes have emerged. Cell surface receptors are activated by specific ligands (eg, C5a, leukotriene B4 [LTB4], CXCL8 [IL-8], and receptor activation is conveyed via specific G proteins. and membrane-bound phospholipases, leading to intracellular calcium mobilization, extracellular calcium influx, and mass phosphorylation of cellular proteins Rare hereditary disease associated with defective receptor and effector defects (eg, IFN- female Insightful insight into receptor malformations and adenine dinucleotide phosphate nicotinamide [reduced form] [NADPH] oxidase defects) have provided into leukocyte function and the importance of such specific activity for host defense.

The primary outcome of neutrophil and monocyte recruitment is the provision of a large number of activated leukocytes that can release lytic agents and reactive oxygen and nitrogen mediators necessary to destroy these pathogens. foreign invaders, and a vehicle containing foreign particles through phagocytosis. Macrophages and recruited memory and effector lymphocytes play an important role in the adaptive immune response. The products and functions of immediately activated inflammatory cells are valued because they contain and destroy invaders and are harmful because they cause tissue damage. Role of neutrophil apoptosis (programmed cell death) in the termination of acute inflammatory responses and IFN-–Driven M1 macrophages and IL-4/IL-13-driven M2 macrophages during the transition from inflammatory tissue to wound-healing or tissue-regenerating tissue discussed in “M1 and M2 Macrophages”.

Activation of leukocytes, especially neutrophils and monocytes, leads to the secretion of microbiological peptides (eg, disinfectants, bactericidal permeability-increasing proteins [BPI]) , cationic antimicrobial proteins [eg, CAP37]) and lytic enzymes (eg, myeloperoxidase, elastase, cathepsin G). The release of these granular components is accompanied by the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates (eg, O 2 - , H 2 O 2 , NO), which give rise to arachidonate metabolites (eg, , leukotrienes and prostaglandins) and production of other inflammatory mediators. In some cases these mediators are released into phagolysosomes where it contributes to the destruction of engulfed bacteria, while in other cases it is secreted into the extracellular environment where it amplifies the response. and cause inflammatory tissue damage. Different types of neutrophil granules (primary azurophilic, secondary specific, containing tertiary gelatinase and secretory vesicles) are released in a different coordinated fashion.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.