This is an automatically translated article.

Posted by Master, Doctor Mai Vien Phuong - Department of Examination & Internal Medicine - Vinmec Central Park International General HospitalShort bowel syndrome is a malabsorption condition that is associated with a high frequency of complications and a high use of healthcare resources. Therefore, in some patients, doctors need to control the amount of food taken into the body, in which the control of sugar, protein, and fat is extremely important.

1. Dietary overview in short bowel syndrome

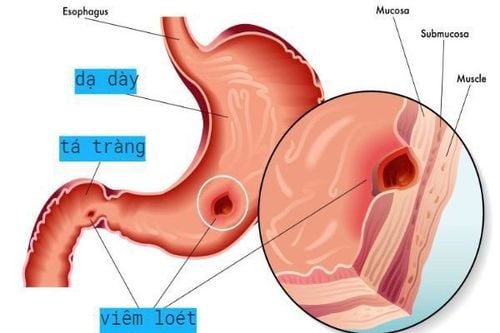

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is a malabsorption condition that is associated with a high frequency of complications and a high use of healthcare resources. The disease usually does not become clinically apparent until about three-quarters of the small bowel (SB) has been resected.Accordingly, without the active use of pharmacological agents, diet is generally not effective in limiting severe diarrhea in patients with short bowel syndrome. However, dietary therapy is an important component of care in these patients. The foundation of dietary therapy is to modify food intake to facilitate maximum nutrient and fluid use by reducing stool volume. Stool output in short bowel syndrome is driven by a fluid load that exceeds the absorptive capacity of the shortened intestine, but other factors also contribute. For example, in addition to the loss of absorptive surface area, the feedback mechanisms that control acid and bicarbonate transport and secretion often suffer. A clear understanding of these factors is essential for selecting the best therapeutic interventions.

MORE: Consequences of short bowel syndrome

2. Assessment of initial nutritional status

The initial evaluation of all patients with short bowel syndrome should include a comprehensive nutritional assessment. Information obtained should include a history of weight change, use of medications (including complementary and over-the-counter medications), the presence of other symptoms that may affect oral or fluid loss, potential signs/symptoms of micronutrient deficiency and physical assessment for signs of dehydration and malnutrition. Additional information that should be collected at baseline includes relevant past medical, psychiatric and surgical history, including comorbidities and the presence of bowel complications such as anastomosis. ; chronic congestion; percutaneous fistula and peritoneal drainage.A history of nutritional support should also be obtained, including information regarding enteral and/or central venous access devices, formulation used, route and method of administration, and complications known before. Finally, given the high levels of motivation required to adhere to prescribed diets, fluids, and medical treatments, it is helpful to inquire about education, motivation, system their support and potential economic barriers.

MORE: How is short bowel syndrome treated?

3. Diet for the treatment of patients with short bowel syndrome

Preliminary evidence demonstrating a beneficial effect of dietary therapy in patients with short bowel syndrome is based on a limited number of studies including a small number of patients with different bowel anatomy. These studies often demonstrate a decrease in stool volume and an increase in absorption, depending on the remaining bowel anatomy and the amount of carbohydrates and fats used. In particular, patients with short bowel syndrome with a remaining segment of the colon appear to derive the most benefit in terms of nutrient absorption and reduced stool loss from a diet high in complex carbohydrates, low in fat and moderate in fat. right.In an inpatient setting, Byrne et al followed nearly 400 patients over a 10-year period following intensive counseling and close follow-up for 2-4 weeks and further demonstrated the importance of the regimen. eating short bowel syndrome on improving stool volume and both nutritional and hydration status. They concluded that colonic patients benefited from a different diet than those without colons.

MORE: Role of Somatropin in Short Bowel Syndrome

4. Controlling the sugar - protein - fat triad for patients with short bowel syndrome

4.1. Fat Fats are an excellent source of calories, but depending on the remaining bowel anatomy in patients with short bowel syndrome, too much fat can exacerbate lipodystrophy, resulting in loss of calories, vitamins, and minerals. fat-soluble and fecal divalent minerals.Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) are often recommended for patients with short bowel syndrome, because they are absorbed directly through the small intestine and large intestinal mucosa. However, it has been shown that only people with residual colons seem to benefit from their use. Furthermore, triglycerides contain fewer calories than dietary fats, have no essential fatty acids, are unpalatable, and do not enhance intestinal adaptation.

4.2. Protein Protein requirements will vary depending on the patient's location during the course of the disease. Protein with high biological value is always preferred over vegetable protein. Because nitrogen absorption is least affected by surface malabsorption in patients with short bowel syndrome. There is no need to change the protein in the diet and the use of a peptide-based diet in these patients is not necessary.

Oral glutamine is often recommended for patients with short bowel syndrome, however, its clinical benefit is controversial and there are insufficient data to support its use in patients with short bowel syndrome. Glutamine is also abundant and readily available in high biological value whole protein foods such as meat, fish, poultry, eggs and dairy.

4.3. Carbohydrates The use of more complex carbohydrates than concentrated sweets reduces stool volume and enhances absorption in short bowel syndrome. Lower in fiber, complex carbohydrates are easier to digest and absorb and should be the primary source of calories/nutrients regardless of remaining gut structure. Patients with a remaining segment of the colon may benefit from a higher soluble fiber content, but not a reduction in oral intake due to early satiety, especially if weight gain is required.

Nutrition therapy is central to the successful management of patients with short bowel syndrome. Continuing and important education to the extent that the patient/carer can be understood from the outset is essential and sufficient time must be devoted to this purpose. As the gut adapts and improves absorption, it is possible that dietary interventions could be released. Lifelong follow-up is necessary in all patients with short bowel syndrome, and management goals often change over time.

Please dial HOTLINE for more information or register for an appointment HERE. Download MyVinmec app to make appointments faster and to manage your bookings easily.

ReferencesJohn K. DiBaise, Carol Rees Parrish, Short Bowel Syndrome in Adults – Part 1 Physiological Alterations and Clinical Consequences, Nutrition issues in gastroenterology, series

132, Practical gastroenterology • august 2014. 1. O'Keefe SJ, Buchman AL, Fishbein TM, Jeejeebhoy KN, Jeppesen PB, Shaffer J. Short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure: consensus definitions and overview. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jan;4:6-10. Dabney A, Thompson J, DiBaise J, et al. Short bowel syndrome after trauma. Am J Surg 2004;188:792-795. 3. Amiot A, Messing B, Corcos O, Panis Y, Joly F. Determinants of home parenteral nutrition dependency and survival of 268 patients with non-malignant short bowel syndrome. Clin Nutr 2013;32:368-374. Thompson JS, DiBaise JK, Iyer KR, et al. Postoperative short bowel syndrome. J Am Coll Surg 2005;201:85-89