This is an automatically translated article.

Posted by Doctor Ho Thi Xuan Nga - Cardiovascular Center - Vinmec Central Park International General HospitalThe method of anesthesia has little effect on infarct rates and patient outcomes; Epidural analgesia, analgesia with vertebral plane analgesia may provide effective protection in the early postoperative period.

1.Pre-anesthesia for coronary patients Use β-blockers for a heart rate of 60-65 beats/min. Maintain antianginal, antiarrhythmic and antihypertensive drugs. ACE inhibitors: Discontinue 24 hours before surgery when indicated for treatment of high blood pressure, maintain if indicated for ventricular dysfunction. Prophylaxis with sedation and anxiolytic with a diazepine. If pain before surgery: morphine + scopolamine. 2. Anesthesia and myocardial ischemia Maintaining mean blood pressure at induction of anesthesia so as not to reduce coronary perfusion, midazolam and propofol do not change the myocardial DO2/VO2 ratio. Etomidate provides the best hemodynamic stability.

Thiopental lowers the DO2/VO2 ratio because it causes tachycardia and hypotension. Ketamine increases VO2 and can cause severe ventricular failure in the case of complete sympathetic blockade.

Halogens cause coronary vasodilation in descending order: isoflurane > desflurane > enflurane > sevoflurane > halothane

Isoflurane: vasodilation and mild tachycardia; risk of coronary thrombosis if Fi > 2 MAC and if hypotension is severe; Sevoflurane: neither hypotension nor tachycardia; Desflurane: sympathetic stimulation, tachycardia, increased systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance Halothane: decreased VO2 due to negative stimulant and negative chronotropic effects (equivalent to β blocker). All halogens confer myocardial protection against ischemia (ischemic pre-adaptation)

Thuốc gây mê Sevoflurane được dùng trong gây mê bệnh nhân thiếu máu cơ tim

3. Anesthesia for coronary patients Two priorities:

Maintain optimal myocardial DO2/VO2 ratio; Early and aggressive treatment of any ischemic episode. Strictly maintain blood pressure (MAP ≥ 80 mmHg) and rate (HR 60-65 beats/min)

Maintain PAM/FC ratio > 1.

Monitor: ECG (D2 and V5) with ST segment monitoring and invasive arterial pressure. Transesophageal echocardiography allows monitoring:

Regional hypodynamics occurs in the case of coronary artery occlusion; Ventricular function and tolerance to hemodynamic changes. Pulmonary artery catheterization is not a technique for monitoring myocardial ischemia. Regional anesthesia and myocardial ischemia:

Spinal anesthesia improves postoperative analgesia and ventilation; it reduces the response to stress, hypercoagulability and post-operative inflammatory syndrome. Its goal was better postoperative comfort for the patient, but it did not significantly change mortality or cardiac risk. On the other hand, the same studies have shown 3 advantages for epidurals:

Very effective pain relief and high quality patient comfort; Reduce lung complications; Reducing thrombosis in vascular and orthopedic surgery. 4. Principles of anesthesia for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Optimization of DO2/VO2 ratio.

Halogen pre-adaptation (Sevoflurane or isoflurane, 1 MAC) before, during, and after IVF

Pre-MI stage: the patient has active myocardial ischemia.

Priority DO2: PAM > 80 mmhg, Hb ≥ 90 gm, FiO2: 0.5; Lower MVO2: HR 50-65 bpm, avoid beta amines; Maintain PAM/FC ratio > 1.

Sử dụng thuốc isoflurane trong giai đoạn tiền thích nghi

Post-MI stage: myocardial reperfusion, but specific risks.

Ventricular dysfunction after MI; Ischemia on surgical problems (anastomosis, flexion, embolism); Incomplete revascularization; Myocardial dizziness, arrhythmia reperfusion; Hemorrhage, acute cardiac tamponade. Fast and comfortable extubation after surgery

5. Ischemia during coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Before MI, the patient had active myocardial ischemia. Risk of ischemia:

Sympathetic stimulation; Lower blood pressure; Fast heart beat; Hibernation. After MI, the principle of coronary perfusion is restored. Causes of ischemia:

Surgical problems (folding, anastomosis); hemodynamic problems (low blood pressure, low flow, acute anemia); Embolism (air, atheroma); Inadequate revascularization; Arterial spasm, tension, flexion of the internal mammary artery; Thrombosis (increased blood clotting); My heart is dizzy. Check the coronary anastomosis by Doppler ultrasound. Cardiac troponin is significant if increased > 5 times.

Bác sĩ có thể kiểm tra miệng nối mạch vành bằng siêu âm Doppler

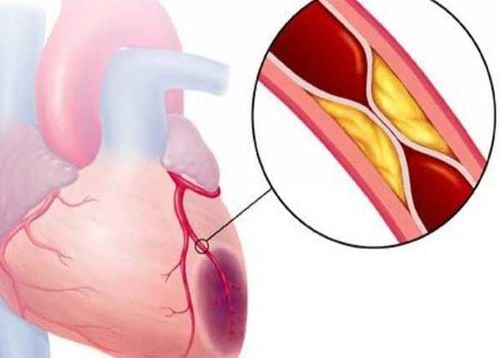

Anesthesia of coronary patients is governed by the need to provide the best possible balance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand, so to keep heart rate low, mean blood pressure between 75 and 80 mmHg , normal preload, low contractility. The aim of this attitude is to prevent ischemia due to excessive demand, which is characteristic of stable coronary stenosis (severe stenosis > 70%); these cause ST-segment depression and most often non-Q-infarcts. Unstable plaques, often less narrow (<60% stenosis), often imbalanced by sympathetic tension (hypertension) pressure, catecholamines, tissue activators) and inflammatory syndromes in surgery. Their rupture leads to local thrombosis, favored by perioperative hypercoagulability; usually causes transmural infarction (STEMI) with Q waves.

After any coronary event (infarction, dilation or bypass surgery) and in the absence of complications, there is a danger period of 6 weeks, during which any operation other than life-threatening emergency is contraindicated. Between 6 and 12 weeks, the risks of surgery are moderate; Mandatory activities are reasonable, provided that the patient is prepared for beta-blockers and continued antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel/prasugrel/ticagrelor) if indicated. The so-called safe period begins three months after passive stenting or coronary artery bypass grafting, but 12 months after acute coronary syndrome or active stents.

Half of postoperative infarctions are related to acute thrombosis of unstable plaques, and not related to the magnitude of coronary stenosis detected by coronary angiography, or to localization. hypoactivity with stress echocardiography. Thus, preparing patients for beta-blockers, antiplatelet drugs, and statins has more impact on their outcomes than preoperative examinations performed. Indications for coronary angiography and revascularization are the same as outside the surgical setting (unstable angina). Percutaneous coronary angioplasty with stenting transforms narrow but stable to unstable stenosis with improved flow, and this over the entire period of intra-stent endothelial remodeling, which lasts from 6 weeks with stents simple metal stents (passive stents) up to 12 months with drug-eluting stents (active stents).

Nong mạch vành qua da bằng kỹ thuật can thiệp tim mạch

The operative period is not the most dangerous, as long as hemodynamic control is strict, since myocardial ischemia occurs mainly in the first two days after surgery. Close hemodynamic monitoring is required, and any deviations in pressure and frequency should be corrected immediately. An ECG change (ST segment change, new conduction block, ventricular arrhythmia) is always significant in this setting and must prompt treatment of acute ischemia. The method of anesthesia has little effect on infarct rates and patient outcomes; Epidural analgesia, analgesia with vertebral plane analgesia may provide effective protection in the early postoperative period. The therapeutic ischemic pre-adaptation effect of halogens confers significant myocardial protection during coronary revascularization; the use of halogens in noncardiac surgery for patients with coronary artery disease is also recommended. report for this purpose. The need for continued maintenance of antiplatelet agents takes precedence over the risk of bleeding and the benefit of local anesthetic in the setting of unstable lesions.

Please see more articles about "Resuscitation anesthesia in ischemic cardiomyopathy and coronary reperfusion" by Doctor Ho Thi Xuan Nga:

Anesthesia resuscitation in ischemic and reperfusion cardiomyopathy Coronary Anesthesia - Part 1 Anesthesia resuscitation in ischemic cardiomyopathy and coronary reperfusion - Part 2 Anesthesia resuscitation in ischemic cardiomyopathy and coronary reperfusion - Part 3 REFERENCES

FLEISHER LA , BECKMAN JA, BROWN KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for non-cardiac surgery: Executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:1707-32 GROSSMAN W, ed. Cardiac catheterization and angiography. 3rd edition. Philadelphia, Lea and Febiger, 1986, 378 KAPLAN Joel.A, Cardiac Anesthesia for cardiac and non-cardiac surgery, 7th edition. Elservier, 2017, 1453-236 KERTAI MD, BOUTIOUKOS M, BOERSMA M, et. Aortic stenosis: An underestimated risk factor for perioperative complications in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Med 2004; 116:8-13 KWAK J, ANDRAWES M, GARVIN S, et al. 3D transesophageal echocardiography: a review of recent literature 2007-2009. Curr Opin Anesthesiol 2010; 23:80-8 MILLER FA. Aortic stenosis: Most cases no longer require invasive hemodynamic study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989; 13:551-8 STS – Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Surgery Database, 2005. http://www.sts.org/documents/pdf/STS-ExecutiveSummary.pdf TIMMIS SB, KIRSH MM, MONTGOMERY DG, STARLING MR. Evaluation of left ventricular ejection fraction as a measure of pump performance in patients with chronic mitral regurgitation. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent 2000; 49:290-7 TORNOS MP, OLONA M, PERMAYER-MIRALDA G, et al. Heart failure after aortic valve replacement for aortic regurgitation: prospective 20-year study. Am Heart J 1998; 136:681-7