This is an automatically translated article.

The article is professionally consulted by Master, Doctor Phan Ngoc Toan - Emergency Medicine Doctor - Emergency Department - Vinmec Danang International Hospital.I. Overview

Shock is defined as cellular and tissue hypoxia due to decreased oxygen supply, increased oxygen consumption, inadequate oxygen utilization, or a combination of these processes. This usually occurs when there is circulatory failure manifesting as hypotension (decreased tissue perfusion); however, patients in shock may present with normal, elevated blood pressure. Initial shock is reversible, but must be recognized and treated immediately to prevent progression to irreversible organ dysfunction and death. "Undifferentiated shock" refers to a situation where shock is recognized but the cause is unclear.In the trauma setting, hemorrhagic hypovolemia is the most common cause of shock. Hypoxia, mechanical obstruction (eg, cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax), neurological dysfunction (eg, high spinal cord injury), and cardiac dysfunction may be causes potential or contributing factors.

Shock is the most common cause of death, second only to traumatic brain injury, and is treatable in trauma patients.

II. Classification and Pathophysiology

1. Classification

Four types of shock are recognized: distributive, cardiovascular, hypovolemic, and obstructive. However, many patients with circulatory failure have a combination of more than one form of shock (mixed shock). There are many causes of the above types of shocks, within the scope of this article, the main common causes will be presented briefly.1.1. Distributive shock : Distributive shock is characterized by severe peripheral vasodilatation (vasodilator shock)

Septic shock : is the most common cause of distributive shock Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) Neurogenic shock : severe traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. Anaphylaxis: most commonly seen in patients with severe immunoglobulin-E (Ig-E)-mediated allergic reactions, to insect stings, foods, and drugs. Drug and Toxic Shock: associated with drug overdose (eg, long-acting narcotics); snake bite; insect bites including scorpions and various spider mites; transfusion reaction; heavy metal poisoning including arsenic, iron and thallium... Endocrine shock: acute adrenal insufficiency, coma and myxedema in severe hypothyroidism... 1.2. Cardiogenic shock: cardiac causes cause acute heart pump failure causing decreased cardiac output, divided into 3 main groups of causes

Cardiomyopathy: myocardial infarction, dilated cardiomyopathy... Arrhythmia: complete atrioventricular block complete, sustained ventricular tachycardia... Mechanical: severe aortic or mitral valve insufficiency, acute valvular defects due to papillary muscle rupture, retrograde dissection of the ascending aorta into the annular aorta (lack of aorta)... 1.3. Volume depletion:

Bleeding: decreased intravascular volume, seen in penetrating or buried trauma, gastrointestinal bleeding, intra-postoperative bleeding, post-sinusectomy, tumor rupture into large blood vessels... No bleeding: decreased intravascular volume due to fluid loss, seen in gastrointestinal dehydration, percutaneous (Steven Johnson syndrome), renal (osmotic diuresis, hypoaldosteronism syndrome), loss into the secondary compartment 3 such as cirrhosis, intestinal obstruction... 1.4. Obstruction: noncardiac causes of acute pump failure usually due to decreased right ventricular output

Pulmonary vasculature: pulmonary embolism, severe pulmonary hypertension Mechanics: reduced preload (reduced left atrial blood flow or ventricular filling). right) seen in tension pneumothorax, pericardial effusion, constrictive pericarditis, restrictive cardiomyopathy. Abdominal compartment syndrome in trauma.

Sốc nhiễm khuẩn là nguyên nhân phổ biến nhất của sốc phân bố

2. Pathophysiology

2.1. Mechanism of shock:Cellular hypoxia causes membrane ion pump dysfunction, intracellular edema, leakage of cytoplasm into the extracellular space, and inadequate regulation of intracellular pH. These biochemical processes, when left unchecked, progress to a systemic level, leading to acidosis and endothelial dysfunction, as well as further stimulation of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cascades. Compounding this process is further reduction of tissue perfusion from complex microcirculatory and microcirculatory processes that reduce blood flow to individual organ systems.

Patients in shock suffer from a severe reduction in the oxygen supply to the mitochondria. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) can still be synthesized by anaerobic glucose hydrolysis, but only at 5 - 10 % of the normal level. Anaerobic metabolism leads to the accumulation of Pyruvate, which is converted to Lactate.

Serum lactate levels, when elevated, have traditionally been used as an indicator of hypoperfusion and tissue hypoxia, and serum lactate levels are a useful risk stratification tool in undifferentiated shock separate.

2.2. Stages of shock:

Pre-shock (compensated): characterized by compensatory responses to tissue perfusion that is currently impaired. For example, in early hypovolemic pre-shock, compensatory tachycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction can allow a healthy adult to be asymptomatic and maintain normal or slightly elevated blood pressure despite a 10% decrease in total blood pressure. arterial blood volume. Therefore, tachycardia, or mild to moderate hyperlactatemia, may be the only clinical signs of early shock. With prompt and appropriate treatment, tissue hypoperfusion can be prevented and signs of impending deterioration can be reversed (eg, normalization of heart rate and serum lactate levels). .

In (progressive) shock: compensatory mechanisms become overwhelmed, signs and symptoms of organ dysfunction appear including symptomatic tachycardia, dyspnea, irritability, acidosis metabolism, sweating, hypotension, oliguria, and cold, moist skin. Signs and symptoms of organ dysfunction often correspond to a significant pathophysiological disorder. For example, in hypovolemic shock, clinical signs and symptoms are associated with a 20 to 25% reduction in arterial blood volume, and in cardiogenic shock, a reduction in the cardiac index to less than 2.5 L/ min/m2 before signs and symptoms appear.

End of shock (decompensation): irreversible organ damage, multiple organ failure and death. Clinically worsens with anuria and progressive acute renal failure, acidosis that depresses cardiac output, hypotension that becomes severe and refractory to treatment, hyperlactatemia worsens, irritation progressing to stupor palpation and coma...Death often occurs during this stage of shock.

Giai đoạn sốc nhược bệnh nhân rơi vào trạng thái suy giảm

III. Shock related to trauma

1. Cause

Bleeding is the most common cause of shock in trauma patients. Massive bleeding can occur in the chest, abdomen, pelvis, retroperitoneal space, and from large external wounds. The thigh can hold up to 1 to 2 L of blood. Scalp lacerations can bleed profusely, especially if the patient is taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs. These injuries may be missed if there is a major head, chest, or abdomen injury or if massive blood loss is present at the scene.Other possible causes of shock other than bleeding in traumatic shock:

Pericardial effusion Tension pneumothorax (Pneumothorax) Pulmonary contusion causing respiratory failure Hemothorax causing respiratory failure Heart injury Spinal cord injury Embolism of fat, air, etc. In penetrating or high-velocity trauma, rupture of the diaphragm complicated by herniation of abdominal viscera and bowel perforation can lead to septic shock. The Guidelines for Advanced Traumatic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (ATLS) practice describe four levels of bleeding to emphasize early signs of shock. Clinicians should be aware that a significant drop in blood pressure often does not manifest until grade III bleeding has progressed, and up to 30% of the patient's blood volume can be lost.

Bleeding grade I : blood loss of about 15%. Minimal or normal increase in heart rate, with no change in blood pressure, pulse pressure, or respiratory rate. Grade II bleeding: blood volume loss of 15 - 30% and is clinically manifested as tachycardia (100 - 120), tachypnea (respiratory rate 20 - 24), decreased pulse pressure, diastolic blood pressure. minimum change. Skin can be cold and moist, prolonging capillary refill time. Grade III bleeding: 30-40% loss, resulting in a significant drop in blood pressure and altered mental status. Any hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg) or a drop in blood pressure greater than 20-30% is a cause for concern. Tachycardia (≥120 beats/min) and respiratory rate markedly increased, while urine output decreased, prolonging capillary refill time. Grade IV bleeding: loss of >40% of blood volume leading to marked hypotension and worsening consciousness, tachycardia (>120), oliguria or anuria. Cold skin, prolonging capillary refill time.

2. Principles for assessing patients with trauma-related shock

Early recognition is the first step in managing injury. Ideally, shock is recognized before hypotension occurs. The clinical presentation of traumatic shock depends on the rate, volume, and time of bleeding, the patient's location, and the presence of other acute pathological processes (eg, tension pneumothorax, ischemic heart disease). In severe trauma, patients often have multiple traumas associated with the development of shock.Initial Survey (Primary Survey) Airway – Breathing – Circulation – Disability – Exposure patient, seek trauma, prevent hypothermia taken directly to the operating room (OR) or angiogram, or transferred to a major trauma center.

Careful, head-to-toe 2nd phase evaluation is performed in all trauma patients determined to be stable after completion of initial assessment. Stage 2 assessment includes detailed history, specific clinical and laboratory examination, and importantly, avoidance of injury.

History - Mechanism of injury may raise suspicion for some injuries. The outpatient clinician usually knows important information and should be asked about the mechanism and history of the injury. If this cannot be done on arrival because of the patient's condition, ask them to remain in the emergency department (ED) until this can be done. Often the history is communicated during patient transport and important information can be forgotten or missed.

While listening, keep in mind that accident scenes can be chaotic and not all information will be reliable. For example, a patient described as "found" may have been assaulted or crashed...

Information regarding mechanism obtained is valuable:

● Concussion injury

Seat belt fastening whole? Steering wheel deformation? Airbag deployment? Direction of impact? Car damage (especially intrusion into the passenger compartment)? Distance splashed out of the car? Fall height? Body part when touching the ground? ● Penetrating trauma

Gun type Distance from gun Number of gunshots resounded Blade type Blade length 2.1 Signs of shock:

Visible and immediately detectable manifestations of a state of shock include:

● Tachycardia (note that neurogenic shock may present with bradycardia)

Low blood pressure

Cold extremities (note that neurogenic shock can occur with warm extremities)

Weak peripheral pulse

● Prolonged capillary refill (> 2 s)

Clamp pressure (<25 mmHg)

● Increased breathing rate

● Change in skin color (eg, paleness, cyanosis)

Altered mental status other than head trauma (can range from coma to agitation)

2.2. Bleeding site:

Bleeding is the most common cause of shock in adult trauma patients. Massive bleeding can occur at 5 common sites:

External bleeding (eg, scalp tear, open fracture)

Thoracic cavity

Peritoneal space

● Retroperitoneal space (usually is caused by a pelvic fracture)

Muscle or subcutaneous tissue (usually from a long bone fracture)

2.3. Laboratory studies: When the cause of shock is unclear, evaluation and treatment occur concurrently.

Focused trauma ultrasound examination (extended - eFAST), performed early in the assessment to look for hemopericardium, intra-abdominal bleeding, and pneumothorax. Trauma radiographs: bedside (thoracic) or traditionally include the chest, pelvis, and lateral cervical spine. A portable chest x-ray and bedside ultrasound can detect injuries that require immediate intervention. Computed tomography: now a powerful tool for trauma investigation Remember that the presence of one injury does not rule out the possibility of other, more serious injuries. Blood tests: The following indications should apply to all patients with traumatic shock:

ABO and Rh blood groups, compatible (preparation of red blood cells, plasma, and platelets for transfusion options). (bulk blood) Complete blood count, blood gas, electrolytes, liver and kidney function Biland coagulation bleeding Depending on the injury and medical history, additional indications may include:

Measurement of blood pressure blood clot elasticity (ROTEM) if possible Urine, Beta HCG Marker on cardiovascular 2.4. Possible medical conditions:

Shock can persist even with "normal" vital signs, making diagnosis difficult. Patients receiving cardiovascular medications such as beta-blockers may not have the typical vital sign response in shock. Young patients with no comorbidities can maintain blood pressure in the normal range despite significant blood loss through vasoconstriction and increased heart rate, only to gradually lose it afterward. Bradycardia for intraperitoneal lesions, possibly vaginally mediated, has been described. In addition, a paradoxical or relative bradycardia has been described in patients with surgical trauma. A retrospective review of more than 1700 trauma patients reported that the absence of tachycardia in the setting of hypoperfusion was associated with a poor prognosis independent of injury severity, systolic blood pressure, and trauma. head injury.

Recognizing shock in the early stages is more difficult, but offers clinicians the opportunity to early reverse visceral hypoperfusion. Ongoing testing and evaluation can detect potential lesions in patients who appear to be "stable" initially after significant trauma.

Alterations in consciousness due to hypoperfusion can initially be subtle and may be difficult to distinguish from drug or alcohol intoxication or associated head trauma. Therefore, increased vigilance for cerebral hypoperfusion must be increased especially in patients with no clear evidence of head injury but altered mental status on or after admission. SpO2, heart rate, and normal capillary glucose measurements in such patients further raise concerns for decreased cerebral perfusion.

In healthy young patients, changes such as agitation, confusion, irritability, indifference to surroundings or inattention to instructions, may be the only signs of early shock. A patient who is "messing up" you and the emergency team may show early signs of shock, not from the effects of toxicity. Be extremely cautious before concluding vital or examination abnormalities are due to non-traumatic or behavioral causes.

Closer examination may provide evidence of early shock. Pale skin or poor capillary filling may represent peripheral vasoconstriction. Sweating can indicate physiological stress and precedes vital sign abnormalities. Slight increase in respiratory rate may reflect compensation for metabolic acidosis. Low urine output may indicate inadequate visceral perfusion. Patients are unable to maintain urine output greater than 0.5 ml/kg per hour and urine concentration can compensate for hypovolemia.

2.5. Emergency management:

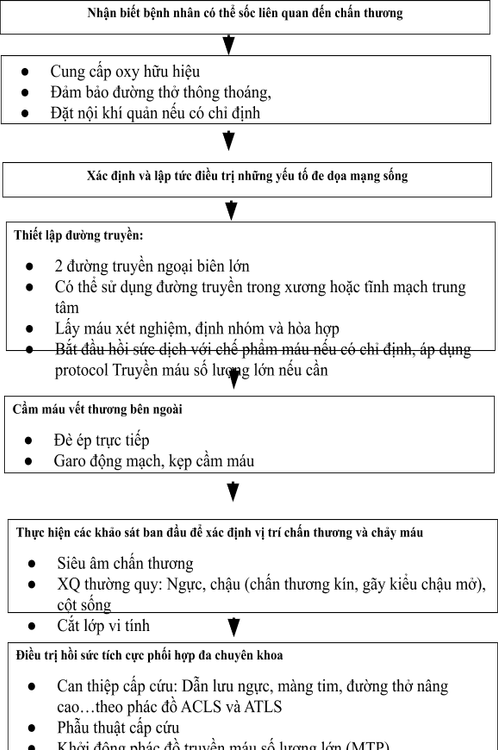

Initial management of adult trauma patients in shock focuses on the following:

Recognition and reversal of life-threatening injuries (eg, pressure pneumothorax) force, cardiac tamponade) immediately Prevent or limit ongoing blood loss Restore intravascular volume if necessary (Molecular solutions, crystals, blood products...) Maintain oxygen supply Depending on the specific situation, if the patient has an out-of-hospital emergency to notify the Hospital, the trauma emergency team is ready to pick up the patient, which can trigger a red alarm (CODE RED). ). If a patient is brought in unannounced or has an emergency on-site, with the above principles in place, clinical practice will be consistent with Initial and Second Assessment, these evaluation steps are repeated during emergency treatment.

Evaluation and treatment are performed concurrently in patients with major trauma. The emergency clinician assesses airway status, hemodynamics, and looks for bleeding sites while performing the following immediate interventions listed in order of preference:

Control bleeding Secure airway ventilation while immobilizing the cervical spine (may be preferred in some situations) Effective oxygen delivery Establish an intravenous line and initiate fluid resuscitation or blood transfusion as indicated Identify and reverse reverse immediate life threats Blood sampling and transfusion planning

Master Phan Ngoc Toan used to work as a Internal Medicine Doctor at Quang Tri General Hospital, Emergency and Intensive Care Doctor - Hoan My Da Nang Hospital before working at Vinmec International General Hospital. Da Nang as it is today. Doctor Math has a lot of experience in the treatment of Resuscitation – Adult Emergency, Pediatric Emergency.

To register for examination and treatment at Vinmec International General Hospital, you can contact Vinmec Health System nationwide, or register online HERE.