This is an automatically translated article.

Posted by Doctor Vu Duy Dung - Department of General Internal Medicine - Vinmec Times City International Hospital

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a type of hemorrhagic stroke and is a neurological emergency with a high morbidity and mortality rate. This article summarizes the most common neurologic and medical complications that are potentially life-threatening to increase the likelihood of early recognition of such complications and the prevention of secondary brain injury.

1. Introduction to Subarachnoid Bleeding

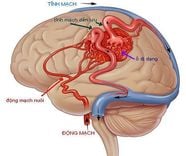

Nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a type of hemorrhagic stroke that is usually caused by rupture of a sacral (berry-shaped) aneurysm and accounts for about 3% of all strokes. While a 17% to 50% reduction in worldwide mortality has been reported in the last 2 to 3 decades, attributed to faster diagnosis and improved treatment strategies, Pre-hospital and 30-day mortality remains high (15% and 35%, respectively). The annual incidence of SAH has not decreased, which is 9/100,000 people in the US and approximately 600,000 cases worldwide.

Despite the decrease in mortality, SAH remains a highly disabling disease. Surviving patients often present with permanent disability, cognitive deficits (especially executive function and short-term memory), and mental health symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety), leading to a A significant reduction in health-related quality of life was reported in 35% of patients one year after SAH. The mean age at the time of aneurysm rupture was 53 years; SAH onset at this age leads to high social costs and many years of lost labor.

2. Causes of Subarachnoid Bleeding

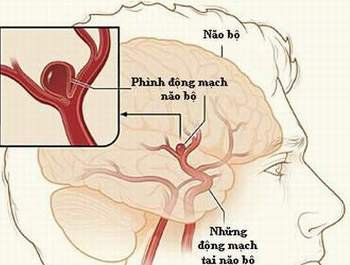

Vỡ phình động mạch não có thể dẫn tới tổn thương cơ tim của bệnh nhân

The most common cause of SAH is rupture of a cerebral aneurysm (85%); however, despite modern neuroimaging techniques, 10% of SAHs do not find a bleeding origin, in which a small fraction (5%) of cases (5%) may have other vascular causes ( eg, arteriovenous malformations, arteriovenous fistulas, reversible cerebral vasospasm syndrome [RCVS]). Particularly in RCVS, high expression of brain convex SAH, rather than SAH in the basal pools, along with typical sausage-shaped areas of constriction/vasodilation on vascular imaging have been described.

Many epidemiological and genetic risk factors for SAH have been identified. Notably, SAH was predominately female (female:male ratio 1.6:1), African-Americans, and Hispanics and Portuguese. High blood pressure, smoking, and heavy alcohol use are modifiable risk factors that double the risk of SAH in a particular individual. Many other genetic and non-modifiable risk factors are also known. Patients are advised to seek counseling about modifiable risk factors to reduce their risk of SAH.

Current guidelines recommend aneurysm screening if the patient has two or more first-degree relatives with aneurysms or SAH. This is based on multiple screening studies spanning the family from the Family Intracranial Aneurysms Study and the International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. Notably, siblings are more likely than children of SAH to have an unruptured intracranial aneurysm.

There have been numerous genomic studies of ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms using genome-wide linkage and association genetic approaches. The AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms also provide a concise overview of current information on genotypes of intracranial aneurysms and SAH. While a meta-analysis of both ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms identified an interleukin-6 (IL6) gene polymorphism at site G572C (on chromosome 7) that increases the risk of aneurysm, no significant genetic risk factors have been identified. Several other single-nucleotide polymorphisms have been associated with aneurysm formation, with the strongest association on chromosome 9 (near the reverse-chain inhibitor CDKN2B), chromosome 8 (near the regulatory gene). copy SOX17), and chromosome 4 (near the EDNRA gene).

Controversy surrounds the heritability of aneurysms and SAH, and many studies, including twin studies, have suggested that environmental risk factors (many of which are modifiable) modifiable) is more important than family genetics or genetic factors. A recent review suggests that familial factors are not comparable to genetic factors because following a family is a subset of risk factors (such as smoking and hypertension). Currently, routine genetic screening is not performed.

SAH remains one of the top neurological emergencies treated in a neurological intensive care unit. Neurologists need to be familiar with this highly disabling pathology, especially in light of the science of acute brain injury after SAH and changes in classical training in etiology. cause of vasospasm and late cerebral ischemia.

The acute phase of SAH can be divided into two: (1) rapid assessment, recognition and diagnosis; immediate referral to the appropriate SAH center; and prompt treatment of the source of bleeding and (2) close follow-up in a neurological intensive care unit with expertise in SAH and comprehensive well-aligned neurologic intensive care with treatment guidelines were available to prevent or ameliorate secondary medical and neurological complications.

Source: Susanne Muehlschlegel. Subarachnoid hemorrhage. CONTINUUM (MINNEAP MINN) 2018;24(6, NEUROCRITICAL CARE): 1623–1657