This is an automatically translated article.

Posted by Doctor Vu Duy Dung - Department of General Internal Medicine - Vinmec Times City International Hospital

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a type of stroke that bleeds into the brain. This is a neurological emergency with a high morbidity and mortality rate. This article focuses on emergency department assessment and management of a patient with SAH.

1. Airway, respiration and circulation

Evaluation and emergency management of patients with SAH should focus on airways, respiration, and circulation (ABCs). Patients unable to protect the airway require immediate intubation, including those who are comatose, stupor due to hydrocephalus, epileptic seizures, or patients requiring sedation due to agitation.

2. Re-bleeding

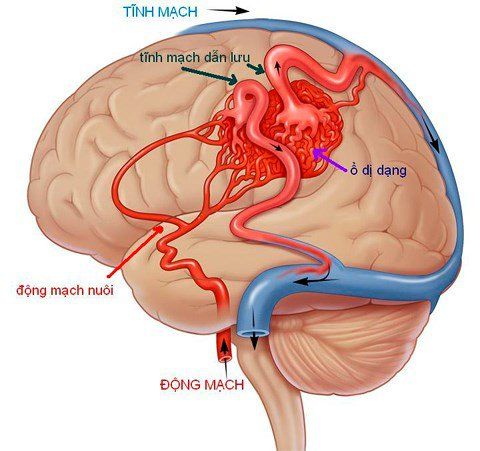

Tăng huyết áp là một trong các nguy cơ tái chảy máu

Within the first few minutes to hours after SAH, until the patient can be treated for ruptured aneurysm, a direct focus should be on preventing rebleeding. This life-threatening complication, with a mortality rate of 20% to 60%, has the highest incidence (8% to 23%) in the first 72 hours after SAH, with the majority of rebleeding (50% to 90%). ) occurred during the first 6 hours, excluding patients who died before arrival at the hospital. After the first month, the rebleeding rate is low, 3% per year. Risk factors for rebleeding include severe SAH, hypertension, large aneurysms, and, potentially, antiplatelet drug use. In particular, blood pressure fluctuations and very high peaks should be avoided as they are thought to have a tendency to cause rebleeding.

The recommendations in current guidelines for blood pressure goals are to keep systolic blood pressure below 160 mmHg. Continuous blood pressure monitoring with an arterial line is strongly recommended. Intravenous drugs for blood pressure control should give preference to a continuous IV blood pressure medication (nicardipine 5 mg/h to 15 mg/h or labetalol 5 mg/h to 20 mg/h) for intravenous administration. bolus (labetalol 5 mg to 20 mg) to prevent blood pressure fluctuations, a predisposing factor for aneurysms to rebleed.

Therefore, at the author's hospital, hydralazine was avoided because it could cause rebound hypertension. Pain control is best achieved with short-acting opiates. Chemical stimulation of the meninges by SAH usually responds to one or more single doses of dexamethasone (2 mg to 10 mg).

3. Anti-fibrinolytic

During prolonged intravenous administration, antifibrinolytics can lead to deep vein thrombosis, venous thrombosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction, so they should not be used, but should be used for a short time. up to 72 hours until aneurysm occlusion) antifibrinolytics (tranexamic acid or ɛ-aminocaproic acid) are recommended based on a randomized controlled clinical trial and several small observational studies. Recently, a large retrospective study including 341 patients over 12 years, in which 146 patients received -aminocaproic acid before endovascular coiling, showed that short-term antifibrinolytic therapy is safe. safe but did not reduce the pre-interventional rebleeding rate. Therefore, there may be hospital variation in the short-term use of antifibrinolytics to prevent rebleeding until a randomized controlled trial confirms or rejects the recommendation. this fox.

4. Disease severity score

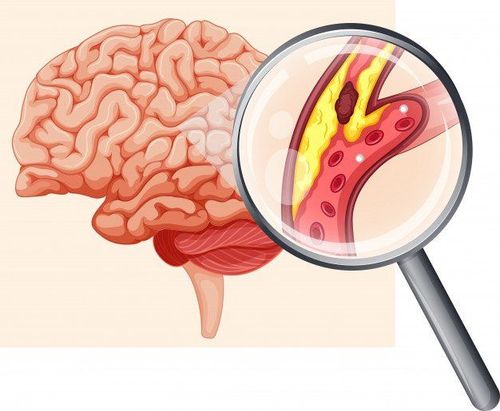

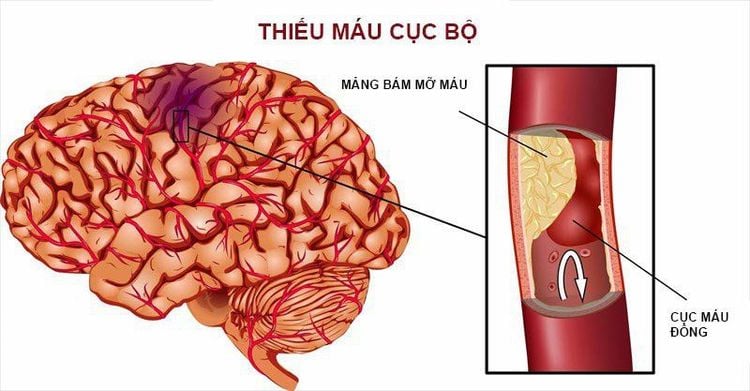

Thiếu máu não cục bộ

The importance of disease severity scores lies in the observation that outcomes and late ischemic events are related to clinical and radiographic grades, respectively. Severity scores provide a common language among all healthcare professionals caring for a patient with SAH. The two most widely used clinical scores, the World Federation of Neurosurgery's score and the Hunt and Hess scale, are strong predictors of outcome. High scores are associated with worse clinical outcomes.

The most validated and reliable electrocardiogram score is the modified Fisher score, which is roughly linearly associated with cerebral vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia.

The classical Fisher scale has many disadvantages and has been widely replaced by the modified Fisher scale. For example, it was developed in the 1980s and thus does not reflect modern multi-layered head CT images. Also, it is nonlinear (Fisher score 3 is associated with a higher risk of vasospasm than Fisher score 4), which interferes with application in the regression model in research and is simply less intuitive when applied at hospital bed.

5. Admission to bulk centers

If the patient is not already in a high-volume SAH specialist center (defined as over 35 SAH cases/year with experienced cerebrovascular surgeons and endovascular specialists and intensive care services), the patient should first be immediately transferred to such a center. Because of the potential lack of standard care and expertise, the admission of SAH patients to small-volume centers is associated with a high mortality rate in the first 30 days. Admission of patients to a neurological intensive care unit staffed by dedicated neurologists is associated with lower hospital mortality in stroke patients, in there is SAH.

6.Treatment of aneurysms

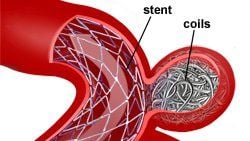

Dùng nút coil nội mạch để điều trị phình động mạch

With the publication of ISAT (International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial), which compared endovascular coiling with clip surgery after SAH, treatment of a converted unobstructed aneurysm from clip-on surgery to mostly endovascular coils. ISAT indicated that patients in the endovascular coiling group had a significantly higher rate of disability-free survival one year after SAH and a lower seizure risk when compared with the surgical clipping group.

Even 10 years after SAH, patients who received endovascular coiling have a better outcome. In contrast, the risk of rebleeding and incomplete occlusion of the aneurysm was lower in the clip surgery group. With the introduction of new techniques such as stent-assisted coiling or ballooning, even wide-neck aneurysms can now be treated with endovascular coiling.

Currently, endovascular coiling is preferred over clip surgery whenever possible. However, follow-up angiography is necessary, as the recurrence rate of aneurysms is higher when they are treated with endovascular coiling.

At the author's hospital, about 95% of aneurysms are treated with endovascular coiling. Many aneurysms are not equally suitable for endovascular coiling or clipping surgery. Treatment options depend on the patient's age as well as the location and morphology of the aneurysm and its relationship to nearby blood vessels. A multidisciplinary approach to prompt treatment decisions with consensus among cerebrovascular surgeons, neurovascular interventions, and neurologists is recommended because complexity of treatment decisions. Regardless of treatment, rebleeding must be prevented, and unobstructed aneurysms should be treated as soon as possible.

7. Active management of subarachnoid hemorrhage

Bệnh nhân bi rối loạn nhận thức

SAH is a systemic and not exclusive disease of the brain. It is often associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (75%), which may be associated with increased inflammatory cytokines. SIRS is associated with persistent cognitive impairment and is associated with nonconvulsive seizures in SAH. SIRS precedes nonconvulsive seizures, and patients with nonconvulsive seizures in the hospital were almost twice as likely to have SIRS as patients without nonconvulsive seizures. Therefore, the negative effect of SIRS on functional outcome is in part thought to be mediated by nonconvulsive seizures.

In addition, patients with SAH are at increased risk for further neurological complications, including hydrocephalus, cerebral edema, delayed cerebral ischemia, rebleeding, epilepsy, and neuroendocrine disorders , which can ultimately lead to dysregulation of sodium, volume, and glucose. Furthermore, hypothalamic-mediated, sympathetic release can induce cardiac and pulmonary complications, including neurogenic ECG changes, arrhythmias, and decreased myocardial contractility (Takotsubo-induced cardiomyopathy). stress), troponin leakage, and myocardial contraction band necrosis. Early recognition and treatment of these complications is key to achieving the best possible outcome for patients with SAH.

Source: Susanne Muehlschlegel. Subarachnoid hemorrhage. CONTINUUM (MINNEAP MINN) 2018;24(6, NEUROCRITICAL CARE): 1623–1657